Late Silurian palynomorphs from the Precordillera of San Juan, Argentina: Diversity, palaeoenvironmental and palaeogeographic significance

VICTORIA J. GARCÍA MURO, CLAUDIA V. RUBINSTEIN, and PHILIPPE STEEMANS

García Muro, V.J., Rubinstein, C.V., and Steemans, P. 2018. Late Silurian palynomorphs from the Precordillera of San Juan, Argentina: Diversity, palaeoenvironmental and palaeogeographic significance. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 63 (1): 41–61.

The palynological content from the Cerro La Chilca and Quebrada Ancha sections of the Wenlock? to Přídolí Los Espejos Formation, in the Argentinean Precordillera is studied. The marine palynomorphs exhibit higher relative abundance and diversity in almost all the productive samples, except for the uppermost ones from both sections, in coincidence with the shift towards more proximal facies in this part. The Los Espejos Formation yielded a total of 114 species of marine organic walled-phytoplankton, 52 species of miospores and two non-marine phytoplankton species. The lower part of the Los Espejos Formation, dated as Ludfordian, displays the highest phytoplankton diversity and the better-preserved palynomorphs of the studied samples in both sections. Diversity tends to diminish towards the upper part of the Los Espejos Formation, dated as late Ludfordian–Přídolí, in coincidence with the transition to storm-dominated shelf and shoreface environments and subaerial exposures that probably hinder the preservation of palynomorphs. Comparisons with coeval phytoplankton assemblages from Gondwana and other palaeoplates such as Laurentia, Baltica, and Avalonia result in strong similarities, which suggest a cosmopolitan distribution pattern during the Ludlow and the Přídolí. Conversely, the trilete spores display more similarities with those from Gondwana and thus suggest a lesser dispersive potential in comparison to phytoplankton. A new trilete spore species Emphanisporites? tenuis is described.

Key words: Organic walled-phytoplankton, miospores, abundance, diversity, palaeoenvironment, palaeobiogeography, Silurian, Argentina.

Victoria J. García Muro [vgarcia@mendoza-conicet.gov.ar] and Claudia V. Rubinstein [crubinstein@mendoza-conicet.gov.ar], IANIGLA, CCT CONICET Mendoza, Av. Ruiz Leal s/n, Parque General San Martín, CC: M5502IRA, Mendoza, Argentina.

Philippe Steemans [p.steemans@ulg.ac.be], Unité de Paléobiogéologie, Paléobotanique et Paléopalynologie, Dpt. de Géologie, Université de Liège, B18/P40 Quartier Agora, Allée du 6 Août, 14, Liège, Belgium.

Received 15 July 2017, accepted 20 October 2017, available online 11 January 2018.

Copyright © 2018 V.J. García Muro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (for details please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The Silurian was considered a relatively stable period, however, in the last decades, several short periods of environmental changes that re-modeled the palaeoceanographic conditions, such as the alternating between humid and arid climates, and oxygen and sulfur cycle variations, were recognized (Munnecke et al. 2003, 2010 and references therein). Accordingly, diversity changes in several marine groups, such as conodonts, graptolites, brachiopods, acritarchs, and chitinozoans were observed (e.g., Jeppsson 1990; Calner 2005, 2008; Lehnert et al. 2007a; Vandenbroucke et al. 2015).

The fossiliferous content of the Los Espejos Formation (Cuerda 1965), including different groups such as graptolites, conodonts, brachiopods, organic-walled phytoplankton, and miospores, has been studied since the 1960s (e.g., Cuerda 1969; Pöthe de Baldis 1974b; Hünicken and Sarmiento 1988; Sánchez et al. 1991, 1995; Benedetto et al. 1992, 1996; Rubinstein 1992a, b, 1995, Rickards et al. 1996; Rubinstein 1995, Rickards et al. 1996; Rubinstein and Brussa 1999). However, biostratigraphically useful fossils, for instance graptolites and conodonts, are scarce and were recorded from isolated fossiliferous levels. The age of the Los Espejos Formation was interpreted, mainly based on brachiopod faunas, as probably Wenlock, mainly Ludlow, Přídolí and up to early Lochkovian in the northernmost outcrops of the stratigraphic unit (Sánchez et al. 1991; Benedetto et al. 1992). A review and update of the palynological information of the Los Espejos Formation was provided by Rubinstein and García Muro (2013).

Based on new palynological data from several sections throughout the basin, a more accurate biostratigraphic scheme was established for the Late Ordovician to Early Devonian of the Precordillera Basin. This new biostratigraphic proposal contributed to the recognition of the Silurian–Devonian boundary as well as to the series and stage boundaries previously located with uncertainty (García Muro et al. 2014a; García Muro and Rubinstein 2015).

Marine phytoplankton clearly dominates the palynological assemblages from the lower to the middle part of the Los Espejos Formation, which correspond to muddy shelf deposits with no influence of wave action. Towards the top of the unit, dated as latest Silurian–Early Devonian, the relative abundance of marine palynomorphs tends to decrease while the miospore relative abundance increases until their predominance in the uppermost productive levels in coincidence with the nearshore environment (Rubinstein and García Muro 2011; García Muro et al. 2014a, b).

From a palaeogeographic point of view, the marine phytoplankton from the Los Espejos Formation points to a cosmopolitan distribution pattern (Rubinstein 1993; Rubinstein and García Muro 2013). Based on studies of the La Chilca Formation, in the Precordillera Basin, the cosmopolitism of the marine palynomorph assemblages was also suggested for the early Silurian (García Muro et al. 2016), when provincialism of marine palynomorphs was assumed to prevail (e.g., Le Herissé and Gourvennec 1995). On the other hand, the terrestrial palynomorph assemblages, especially the trilete spores of the Los Espejos Formation, have more species in common with assemblages from other Gondwana basins located closer to the Precordillera (García Muro et al. 2014b).

The aim of this work is to comprehensively present and analyse the well-preserved organic-walled phytoplankton and miospores from two sections of the Los Espejos Formation, situated at the Cerro La Chilca and the Quebrada Ancha localities; to evaluate the diversity trends in relation to the local palaeoenvironment; and to correlate the studied assemblages with worldwide coeval palynological assemblages enabling palaeobiogeographical inferences. Moreover, many species are herein reported for the first time from Argentina and also from Gondwana, therefore providing new insights regarding palynomorph distribution patterns.

Institutional abbreviations.—IANIGLA, Instituto Argentino de Nivología, Glaciología y Ciencias Ambientales, Mendoza, Argentina; CCT, Centro Científico Tecnológico, Mendoza, Argentina; CONICET, Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas; FNRS, Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique, Liège, Belgium; MPLP, Mendoza-Paleopalinoteca-Laboratorio de Paleopalinología, IANIGLA, Mendoza, Argentina.

Geological setting

The active margin of Western Gondwana was affected by the Cuyania terrane accretion during the Mid–Late Ordovician (Benedetto 2010 and references therein). This collision greatly influenced the subsequent Silurian and Devonian deposits of the Central Precordillera of San Juan, resulting in the formation of the Talacasto-Tambolar arch. The stratigraphic units wedged towards this arch and important interruptions of sedimentation took place (Astini et al. 1995).

The Silurian to Lower Devonian rocks of the Central Precordillera crop out with a north-south arrangement. They are represented in the Tucunuco Group, which is composed of the lower La Chilca Formation and the upper Los Espejos Formation (Fig. 1). The thickness of the Los Espejos Formation reaches 500–600 m in the northern Jáchal area and decreases southwards down to 50 m near the Río San Juan (Sánchez et al. 1991; Astini and Maretto 1996; Benedetto et al. 1996). A transgressive to high sea-level stand history was interpreted for the unit based on the presence of a thin iron veneer and phosphate-rich chert conglomerate at the base succeeded by shaly intervals deposited in a low energy open shelf. Upward, the stratigraphic unit gets thicker and coarser, what is consistent with the transition to a storm-dominated inner shelf to shoreface environment (Sánchez et al. 1991; Astini and Maretto 1996; Benedetto et al. 1996).

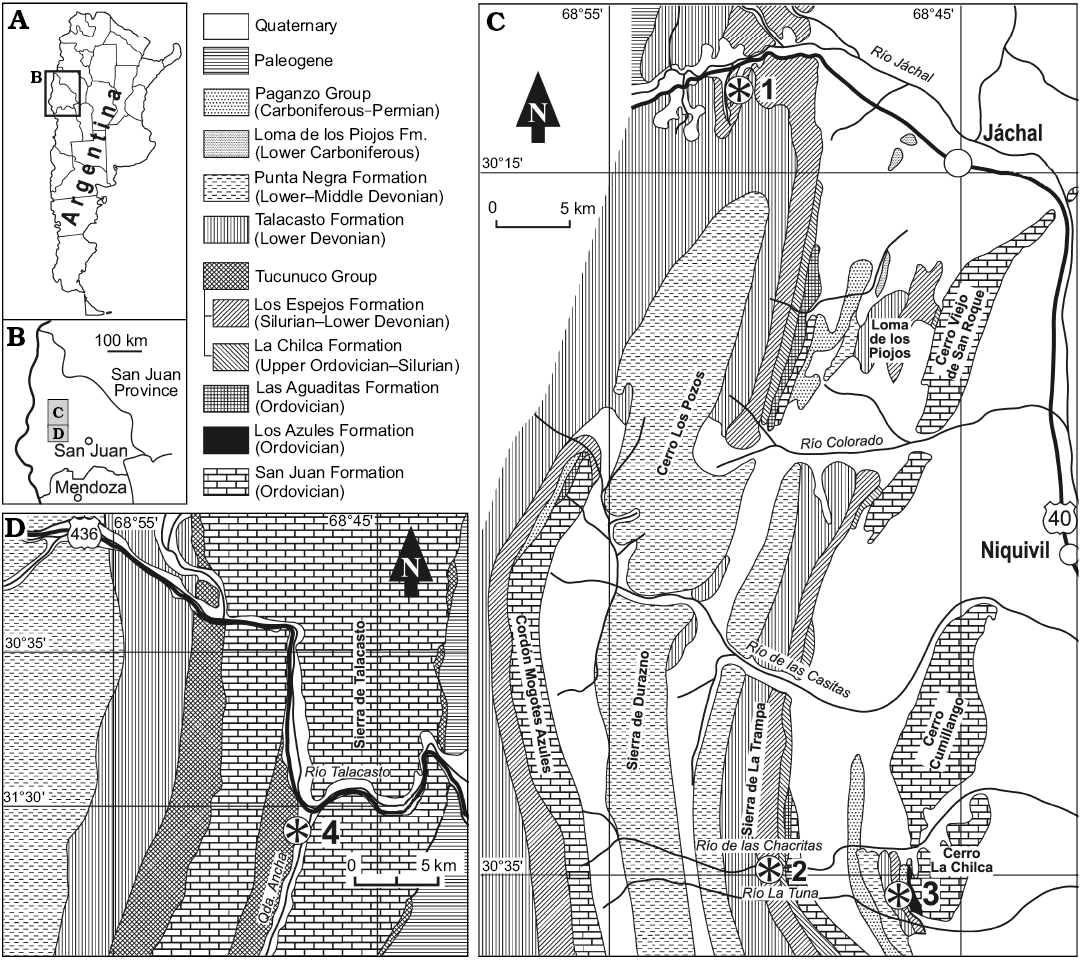

Fig. 1. A, B. Geographic location of study areas. C, D. Geologic maps showing the fossil localities (asterisks). The northern and middle (C) and southern (D) part of the Silurian–Devonian Basin. 1, Río Jáchal; 2, Río de las Chacritas; 3, Cerro La Chilca (this paper); 4, Quebrada Ancha (this paper).

Material and methods

The studied areas are located at Cerro La Chilca and Quebrada Ancha, in the middle and southern part of the Silurian–Devonian basin, respectively (Fig. 1). The samples from the Cerro La Chilca section (30°36’3,1” S; 68°47’32,2” W) were collected from the olive-green pelite of the lower 12 m of the Los Espejos Formation (Fig. 2) principally to constrain the age of the contact with the underlying La Chilca Formation (García Muro and Rubinstein 2015).

In the Quebrada Ancha locality (31°2’13” S; 68°45’55.33” W), two sections corresponding to the lower and upper parts of the stratigraphic unit were sampled to accurately date the lower and upper contacts with the La Chilca Formation and the Talacasto Formation, respectively. The lower 27 m of the unit comprise pelitic sediments that represent a low-energy open shelf environment (Fig. 3B, C). The upper 8 m, below the top of the unit (Fig. 3A), consist of pelitic sediments with intercalated sandstone and shell beds related to storm-dominated shelf and shoreface environments (Sánchez et al. 1991; Astini and Maretto 1996).

Seven samples were collected from the Cerro La Chilca section and 18 from the Quebrada Ancha section. Almost all the samples proved to be productive, except for the uppermost four from the upper Quebrada Ancha section (Figs. 2, 3).

The samples were prepared at the Palynology Laboratory of the University of Liège (Belgium). The rock samples were treated with HCl-HF-HCl acid maceration techniques (Traverse 2007). The residues were oxidized with 60% of Schulze solution (HNO3+KClO3) for two hours and then screened on a 12 µm sieve.

A minimum of 250 specimens per sample was counted in order to obtain the relative abundance of the different palynomorph groups throughout the section and compare fluctuations in palynomorph distribution with changes in the depositional environment (De Vernal et al. 1987; Vecoli et al. 2009).

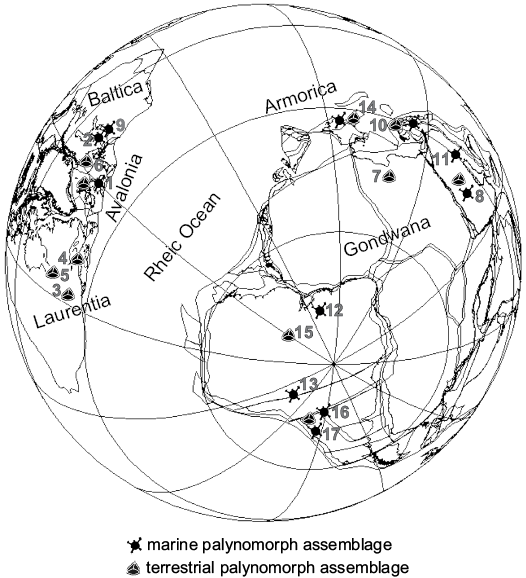

The comparison of the Quebrada Ancha and the Cerro La Chilca palynomorph assemblages with coeval assemblages from Gondwana and other palaeoplates, such as Armorica, Avalonia, Baltica, and Laurentia enabled the identification of species in common and the consequent recognition of palaeobiogeographic trends. Selected phytoplankton and miospore assemblages were plotted on a palaeogeographical reconstruction using BugPlates software (Torsvik 2009) at 424 My and subsequently improved in graphic software.

The terrestrial palynomorphs of the Los Espejos Formation from the Quebrada Ancha locality were published in detail in García Muro et al. (2014b). In the present contribution, special emphasis is therefore placed on the marine palynomorphs.

The organic-walled phytoplankton and the miospore taxa from both sections of the Los Espejos Formation are alphabetically listed and ordered in the Appendix 1 according to Le Hérissé et al. (2009) and Wellman et al. (2015). Some remarks are provided in case of doubtful assignments or differences with the original diagnosis of the species. The stratigraphic distribution of the recorded species is provided by section and level in the SOM (Supplementary Online Material available at http://app.pan.pl/SOM/app63-GarciaMuro_etal_SOM.pdf). All the species are illustrated in Figs. 5–11, except those taxa already illustrated for the Quebrada Ancha and Cerro La Chilca sections (García Muro et al. 2014b; García Muro and Rubinstein 2015) and some taxa left in open nomenclature.

The palynological slides are housed in the palaeopalynological collection MPLP (Mendoza-Paleopalinoteca-Laboratorio de Paleopalinología) at IANIGLA, CCT CONICET Mendoza, Argentina. Specimen locations are referred to by using England Finder coordinates between brackets.

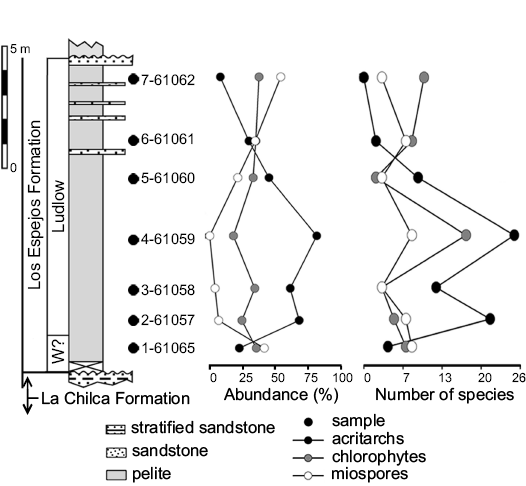

Fig. 2. Stratigraphic section of the Los Espejos Formation in Cerro La Chilca, showing relative abundance (%) and diversity (number of species) of acritarchs, chlorophytes, and miospores per sample. W?: Wenlock?

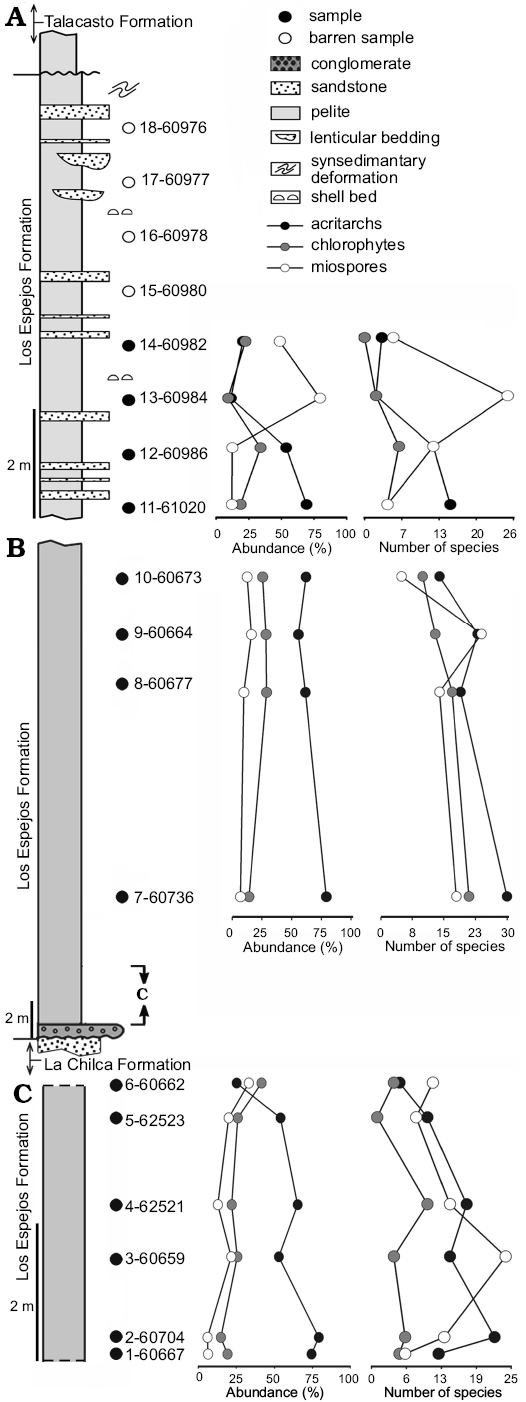

Fig. 3. Stratigraphic section of the Los Espejos Formation in the Quebrada Ancha area upper (A) and lower (B, C) parts, showing relative abundance (in %) and diversity (number of species) of acritarchs, chlorophytes, and miospores per sample.

Results

The marine phytoplankton is more diverse than the miospores in most of the samples from the studied sections at Cerro La Chilca and Quebrada Ancha. In samples MPLP 4-61059 from the Cerro La Chilca section and MPLP 7-60736 from the Quebrada Ancha section, the highly diverse and exceptionally well-preserved assemblages compared to the general preservation of the Silurian and Devonian palynomorphs from the Argentinean Precordillera, are of special interest. The samples from the Cerro La Chilca section contained a total of 44 species of acritarchs, 24 of chlorophytes, 19 of miospores and two non-marine phytoplankton species (Fig. 2). The lower part of the Quebrada Ancha section yielded the most diversified assemblages, with 71 species of acritarchs, 39 of chlorophytes, 49 of miospores, and one of non-marine phytoplankton (Fig. 3B, C). With 19 species of acritarchs and 9 of chlorophytes as well as 28 of miospores denoting an important increase of terrestrial influence, the upper part of the Quebrada Ancha section yielded relatively poorly preserved palynomorphs compared to the lower part of the section (Fig. 3A).

The organic-walled phytoplankton exhibits higher abundance than the terrestrial palynomorphs in most samples from both localities. Miospores become dominant towards the top of the sections, what is consistent with previous sedimentological and palaeoenvironmental studies that indicate a shallowing trend upward the sequence.

Some levels reveal higher relative abundance of terrestrial palynomorphs even though there are no evident changes in the sedimentary record, for instance an increase of terrestrial input, which could explain this variation between marine and terrestrial palynomorph abundances. Such is the case of sample MPLP 1-61065 in the Cerro La Chilca section and sample MPLP 6-60662 in the Quebrada Ancha section (Figs. 2, 3B, C).

The comparison of the marine phytoplankton from both sections of the Los Espejos Formation with coeval assemblages (Table 1, Fig. 4) indicates that more than half of the species are shared with Avalonia (e.g., Mullins 2001 and references therein; Richards and Mullins 2003) and Baltica (e.g., Porębska et al. 2004; Stricanne et al. 2006). Around 20% of the species are common to Armorica (e.g., Cramer 1964a) and Laurentia (e.g., Cramer 1970; Mullins 2001 and references therein), and almost 30%, to other Gondwanan regions (e.g., Le Hérissé et al. 1997; Cardoso 2005). On the other hand, the miospore assemblages of the Precordillera share more species with coeval assemblages from other Gondwanan and peri-Gondwanan areas such as North Africa, Brazil, and Spain (e.g., Richardson et al. 2001; Rubinstein and Steemans 2002; Steemans et al. 2008). Besides, the Cerro La Chilca and Quebrada Ancha studied sections yielded 12 species of phytoplankton which were recognized for the first time for Gondwana. Ammonidium maravillosum, Cymatiosphaera acuminata, Cymatiosphaera lawsonii, Dilatisphaera cf. williereae, and Helosphaeridium malvernense were previously recorded only from Avalonia and Baltica (Cramer 1970; Lister 1970; Dorning 1981; Mullins 2001).

Table 1. Marine and terrestrial taxa (in %) from the Los Espejos Formation (Precordillera Argentina) also present in coeval palaeoplates worldwide and in other Gondwanan localities.

| |

Marine palynomorphs |

Terrestrial palynomorphs |

|

Armorica |

19.81 |

38.46 |

|

Avalonia |

53.77 |

38.46 |

|

Baltica |

59.43 |

33.33 |

|

Gondwana |

27.35 |

56.41 |

|

Laurentia |

20.75 |

17.94 |

Fig. 4. Ludlow–Přídolí (424 My) phytoplankton and miospore assemblages plotted on a palaoegeographic reconstruction using BugPlate software (Torsvik 2009). 1, UK (Richardson and Lister 1969; Lister 1970; Richardson et al. 1981; Burgess and Richardson 1995; Wellman and Richardson 1996; Richards and Mullins 2003; Mullins 2001, 2004); 2, Gotland, Sweeden (Stricanne et al. 2004; Stricanne et al. 2006); 3, Allenport, USA (Beck and Strother 2008); 4, Nova Scotia, Canada (Beck and Strother 2001); 5, Ontario, Canada (McGregor and Camfield 1976); 6, Sweden (Mehlqvist et al. 2012; Mehlqvist et al. 2014); 7, Libya (Richardson and Ioannides 1973; Rubinstein and Steemans 2002; Le Hérissé 2002); 8, Saudia Arabia (Le Hérissé et al. 1995; Wellman et al. 2000; Breuer et al. 2017); 9, Poland (Porębska et al. 2004); 10, Turkey (Steemans et al. 1996; Lakova and Göncüoğlu 2005); 11, Iraq (Al-Almeri 1984; 2010); 12, Maranhão Basin, Brazil (Brito 1967); 13, Bolivia (Cramer et al. 1974; Kimyai 1983; Racheboeuf et al. 2012); 14, Spain and West France (Rodríguez González 1978; 1983; Steemans 1989; Cramer 1964a; Richardson et al. 2001); 15, Amazon Basin, Brazil (Cardoso 2005; Steemans et al. 2008); 16, Santiago del Estero, Argentina (Pöthe de Baldis 1974a); 17, Precordillera Argentina (Rubinstein 1992a, b, 1995; García Muro et al. 2014b; this contribution). References discussed in the papers are also included.

Systematic palaeontology

Marine Chlorophytes

Prasinophytes

Genus Melikeriopalla Tappan and Loeblich, 1971

Type species: Melikeriopalla amydra Tappan and Loeblich, 1971; Waldron Formation, Indiana, USA; Wenlock.

cf. Melikeriopalla sp.

Fig. 9A–F.

Material.—14 specimens measured. Samples MPLP 1-61065 (U47/2, W30/3); MPLP 3-61058 (L33); MPLP 6-61061 (M31/3); MPLP 7-61062 (D39, D45/3, P43/3, P50/3); MPLP 2-60704 (L26/4); MPLP 3-60659 (F38/3, R38/1); MPLP 4-62521 (T40/4, T40/4); MPLP 6-60662 (J25/2). Vesicle divided into filds by muri. Homerian–Ludfordian of Argentina. Cerro La Chilca and Quebrada Ancha localities, Los Espejos Formation.

Description.—Vesicle square to sub-spherical, divided into 6–13 polygonal fields by thick muri. Each field is ornamented by a ring and/or a granum; when both are present the granum is located in the center of the ring.

Dimensions.—Vesicle 16–(23)–30 µm, fields 6–(9)–12 µm, muri high 0.3–1 µm, grana high 0.5–(1)–3 µm, grana diameter 1–(3)–5 µm, rings high 0.3–(0.5)–1 µm, rings thick 0.5–(1.5)–3 µm (14 specimens measured; number in brackets is the mean value).

Discussion.—According to the emended diagnosis of Mullins (2001), in the centre of each field a circular node beneath which a pore may or may not be present. Because of the poor preservation, the pore cannot be observed in the specimens from the Los Espejos Formation. The genus was assigned with doubts because no ring was described for Melikeriopalla.

Non-marine palynomorphs

Zygnemataceae

Genus Clypeolus Miller, Playford, and Le Hérissé, 1997

Type species: Clypeolus tortugaides (Cramer, 1966a) Miller, Playford, and Le Hérissé, 1997; León, Spain; Llandovery.

Clypeolus tortugaides (Cramer, 1966a) Miller, Playford, and Le Hérissé, 1997

Fig. 5O.

Material.—One specimen recorded. Sample 4-62521 (V42/2). Subcircular vesicle, divided in fields by the concavo-convex wall. Ludfordian of Argentina. Quebrada Ancha locality, Los Espejos Formation.

Remarks.—It is considered as a fresh water palynomorph, from transitional marine-freshwater environment (Le Hérissé et al. 2013). The specimen from the Los Espejos Formation constitutes the first record of South America.

Stratigraphic and geographic range.—It was only recognized in the Upper Ordovician of Chad (Le Hérissé et al. 2013) and Canada (Delabroye et al. 2011), in the middle Llandovery of Saudi Arabia and in the Silurian of Spain (Miller et al. 1997 and references therein).

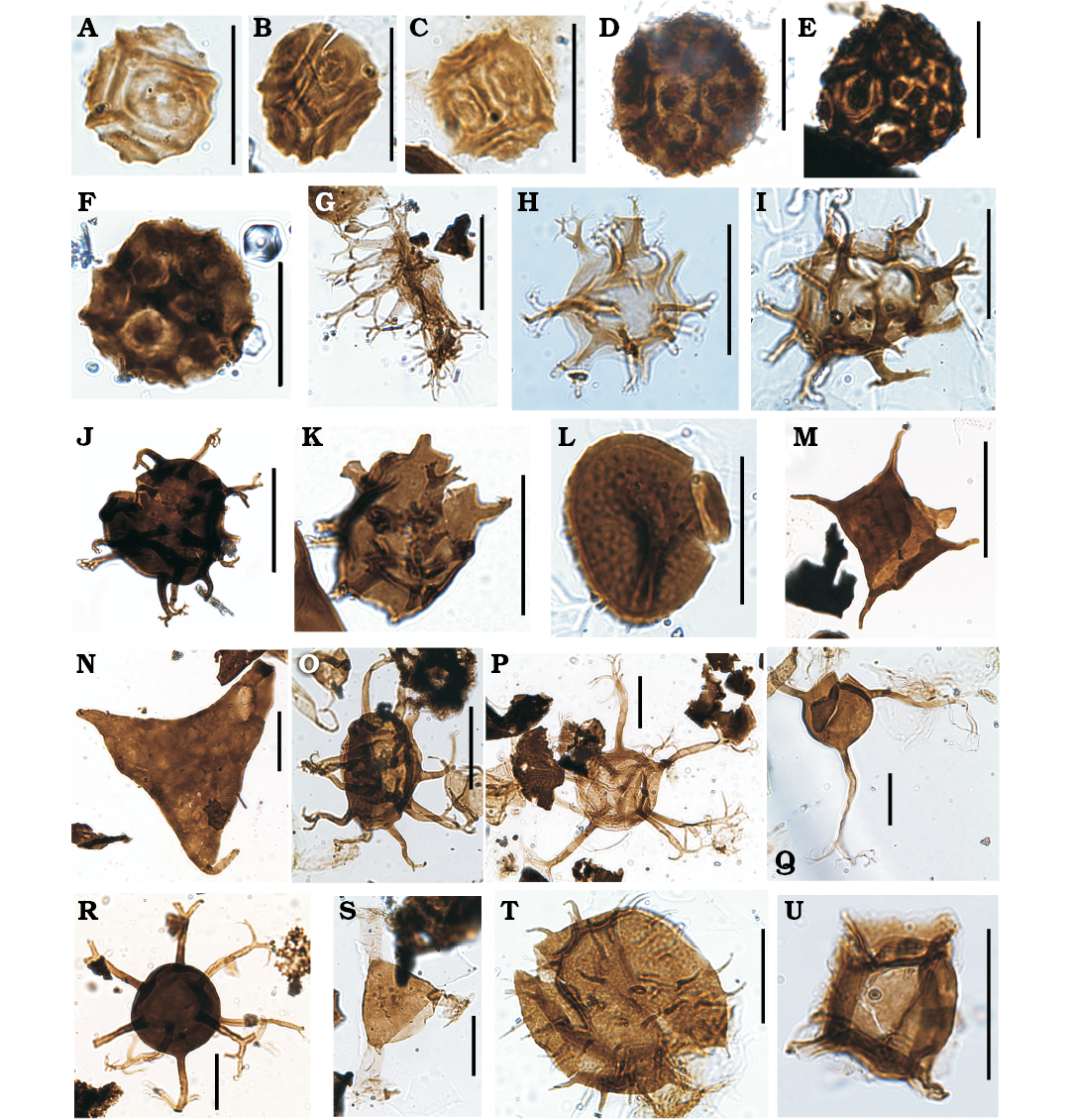

Fig. 5. Palynomorphs from the studied sections of the Los Espejos Formation of Argentina, Quebrada Ancha, Gorstian?–Ludfordian? (A, T), Quebrada Ancha, Ludfordian (B–F, H–K, N, O, Q, R), Cerro La Chilca, Ludfordian (G, L, M, P, S). A. Ammonidium cornuatum Loeblich and Wicander, 1976; MPLP 8-60677 (H27/3). B. Ammonidium ludloviense (Dorning, 1981) Mullins, 2001; MPLP 2-60704 (T22/2). C. Ammonidium maravillosum (Cramer, 1969) Thusu, 1973a; MPLP 7-60736 (S29/1). D. Ammonidium waldronense (Tappan and Loeblich, 1971) Dorning, 1981; MPLP 8-60677 (T50/2). E. Ammonidium sp. A in Mullins 2001; MPLP 7-60736 (N27/1). F. Indeterminated miospore, MPLP 8-60677 (O44/2). G. Baculatireticulatus baculatus Al-Ameri, 1984; MPLP 4-61059 (J45/4). H. Baculatireticulatus sp.; MPLP 7-60736 (N43/2). I. Breconisporites sp.; MPLP 8-60677 (U33). J. Buedingiisphaeridium lunatum Le Hérissé, 1989; MPLP 4-61059 (D47). K. Carminella maplewoodensis Cramer, 1968; slide MPLP 7-60736 (R26/2). L. Chelinospora cf. cantabrica Richardson, Rodríguez, and Sutherland 2001; MPLP 5-61060 (U38). M. Chelinospora sanpetrensis (Rodríguez, 1978) Richardson, Rodríguez, and Sotherland 2001; MPLP 7-61062 (C35). N. Chelinospora verrucata var. verrucata Morphon in García Muro et al., 2014b; slide MPLP 8-60677 (K43/1). O. Clypeolus tortugaides (Cramer, 1966a) Miller, Playford, and Le Hérissé, 1997; MPLP 4-62521 (V42/2). P. cf. Concentricosisporites agradabilis (Rodríguez, 1978) Rodríguez, 1983; MPLP 6-61061 (H45/1). Q. Confossuspora sp.; MPLP 2-60704 (O42/1). R. Cordobesia uruguayensis (Martinez-Macchiavello, 1968) Pöthé de Baldis, 1977; MPLP 3-60659 (E46/4). S. Coronaspora cromatica (Rodríguez, 1978) Richardson, Rodríguez, and Sutherland, 2001; MPLP 4-61059 (Q28). T. Cymatiosphaera acuminata Mullins, 2001; MPLP 8-60677 (G48/3). Scale bars 20 µm.

Trilete spores

Genus Emphanisporites McGregor, 1961

Type species: Emphanisporites rotatus (McGregor, 1961) emend. McGregor, 1973; Quebec, Canada; Lower Devonian.

Emphanisporites? tenuis sp. nov.

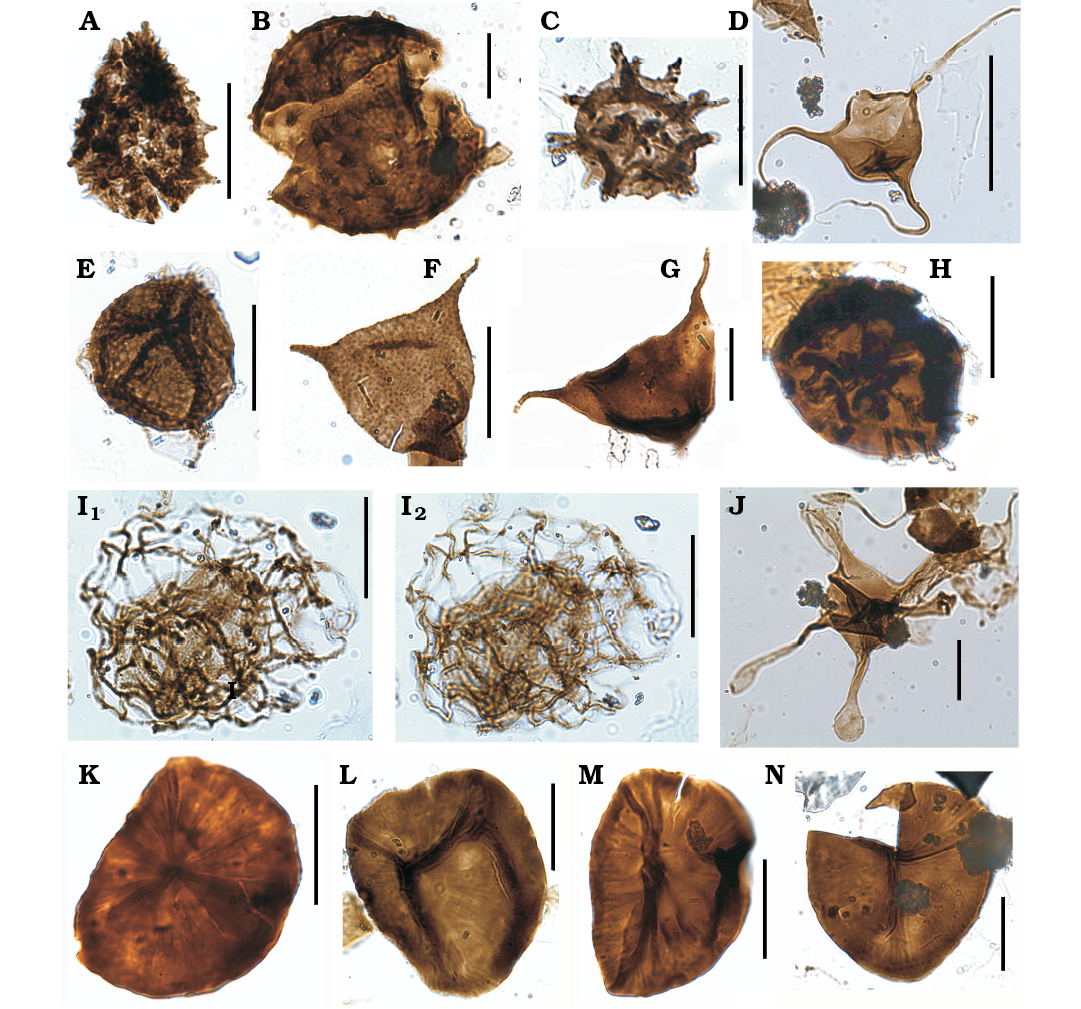

Fig. 11K–N.

1981 Emphanisporites sp. D; Richardson et al. 1981: 215, pl. 1.3.

2008 Emphanisporites sp. D Richardson, Rasul, and Al-Ameri, 1981; Steemans et al. 2008: 274, figs. 8–10.

2014 Emphanisporites sp. D Richardson et al. 1981; García Muro et al. 2014b: 485, fig. 8f.

2015 Emphanisporites sp. D Richardson et al. 1981; García Muro and Rubinstein 2015: 272, fig. 3.7.

Etymology: From Latin tenuis, tenuous; in references to the characteristic thin ribs.

Type material: Holotype: MPLP 13-60984 (N30/2) (Fig. 11K). Paratype: MPLP 2-61065 (Q42) (Fig. 11L) from Cerro La Chilca section.

Type locality: Quebrada Ancha upper section, Los Espejos Formation, San Juan, Argentina (Fig. 1D, 4).

Type horizon: Storm-dominated inner shelf environment of the Los Espejos Formation, Přídolí.

Material.—Seven specimens measured. Samples MPLP 1-61065 (O28/3); MPLP 2-61057 (O47/1; Q42/1, U27); MPLP 2-60704 (K38/4), MPLP 9-60664 (S28), MPLP 10-60673 (J23/1). Wenlock?–Přídolí of Argentina, Cerro La Chilca and Quebrada Ancha localities, Los Espejos Formation.

Diagnosis.—Trilete patinate spore with numerous tenuous ribs on the proximal face.

Description.—Trilete patinate spore with subtriangular to subcircular amb. The thickness of the patina is variable. Laesure straight, extends to the equator, accompanied by labra about 2–4 μm in overall width. Equatorially thickened, 2–4 μm wide. Proximally, 18–26 ribs of less than 1μm of width per interradial area, extending to the patina.

Dimensions.—42–(50)–55μm (7 specimens measured).

Remarks.—Other species of Emphanisporites differ in presenting broader radial ridges and having no patina. Artemopyra inconspicua Breuer, Al-Ghazi, Al-Ruwaili, Higgs, Steemans, and Wellman, 2007 is ornamented by similar thin radial ribs in the hilum but lacks the trilete mark and the patina. According to the original diagnosis of McGregor (1961), the genus Emphanisporites does not comprise patinate forms. Possibly, a new genus should be considered for the specimens included in Emphanisporites? tenuis although the specimens are not enough to create it in the present contribution.

Stratigraphic and geographic range.—Richardson et al. (1981) recorded Emphanisporites sp. D from the late Ludlow of Libya and the early Přídolí of England and Wales but did not describe the species and the latter was not even illustrated. Lochkovian of the Amazon Basin, Brazil (Steemans et al. 2008). Wenlock? to Přídolí of the Precordillera, Argentina (García Muro et al. 2014b; García Muro and Rubinstein 2015).

Indeterminate organic-walled phytoplankton

Fig. 11I.

Material.—One specimen recorded. Sample 4-61059 (G35/4). Ludfordian of Argentina. Cerro La Chilca locality, Los Espejos Formation.

Description.—Spherical vesicle with granulated wall, enclosed in a reticulate envelope, without connection to the vesicle.

Remarks.—Even though it is well preserved, only one specimen was recovered and there are not palynomorphs with similar morphology in the literature; thus, hindering its classifications.

Fig. 6. Palynomorphs from the studied sections of the Los Espejos Formation of Argentina, Quebrada Ancha, Přídolí (A, B, D, H, N), Quebrada Ancha, Ludfordian (C, E, F, I, J, L, O–Q), Cerro La Chilca, Ludfordian (G, K, M, R, S). A. Cymatiosphaera cf. densisepta Le Hérissé, 2000; MPLP 10-60673 (J43/1). B. Cymatiosphaera heloderma Cramer and Díez, 1972; MPLP 9-60664 (X27/2). C. Cymatiosphaera jardinei Cramer and Díez, 1976; MPLP 8-60677 (U51/3). D. Cymatiosphaera lawsonii Mullins, 2001; MPLP 9-60664 (O28/3). E. Cymatiosphaera aff. ledburica Mullins, 2001; MPLP 7-60736 (L41/2). F. Cymatiosphaera cf. mirabilis Deunff, 1959; MPLP 8-60677 (U50/1). G. Cymatiosphaera multicristata Mullins, 2001; MPLP 4-61059 (G28/2). H. Cymatiosphaera aff. multisepta Deunff, 1955, Mullins, 2001; MPLP 10-60673 (K46/3). I.Cymatiosphaera nimia Le Hérissé, 2002; MPLP 8-60677 (T50/1). J. Cymatiosphaera octoplana (Downie, 1959) Mullins, 2001; MPLP 7-60736 (Q32/2). K. Cymatiosphaera paucimembranae Mullins, 2001; MPLP 6-61061 (P36/2). L. Cymatiosphaera prismatica (Deunff, 1954) Deunff, 1961; MPLP 7-60736 (G47/2). M. Cymatiosphaera salopensis Mullins, 2001; MPLP 7-61062 (J38/3). N. Cymatiosphaera sp.; MPLP 10-60673 (E41/1). O. Cymbosphaeridium cariniosum (Cramer, 1964a) Jardine, Combaz, Magloire, Peniguel, and Vachey, 1972; MPLP 2-60704 (T43). P. Cymbosphaeridium pilar (Cramer, 1964a) Lister, 1970; MPLP 4-62521 (D42/1). Q. Cymbosphaeridium sp. A Mullins, 2001; MPLP 8-60677 (T51/4). R. Dactylofusa maranhensis Brito and Santos, 1965; MPLP 4-61059 (G33/3). S. Dactylofusa cf. striatogranulata Jardiné, Combaz, Magloire, Peniguel, and Vachey, 1974; MPLP 4-61059 (L44). Scale bars 20 µm.

Fig. 7. Palynomorphs from the studied sections of the Los Espejos Formation of Argentina, from Cerro La Chilca, Ludfordian (A, M, O), Cerro La Chilca, Gorstian?–Ludfordian? (B, N, P, S), Quebrada Ancha, Ludfordian (C, D, F, H, J, K, L, Q, R), Quebrada Ancha, Přídolí (E, G, I), Quebrada Ancha, Gorstian?–Ludfordian? (T). A. Dateriocradus lindus (Cramer and Díez, 1976) Sarjeant and Vavrdová, 1997; MPLP 4-61059 (Q42/3). B. Dictyotidium alveolatum (Kiryanov, 1978) Le Hérissé, 1989; MPLP 2-61057 (O41). C. Dictyotidium biscutulatum Kiryanov, 1978; MPLP 7-60736 (Q27). D. Dictyotidium callum Al-Ruwaili, 2000; MPLP 3-60659 (P45/1). E. Dictyotidium dictyotidium (Eisenack, 1938) Eisenack, 1955; MPLP 12-60986 (J28/4). F. Dictyotidium faviforme Schultz, 1967; MPLP 2-60704 (H38/3). G. Dictyotidium stellatum Le Hérissé, 1989; MPLP 10-60673 (D39/3). H. Dictyotidium tenuiornatum Eisenack, 1955; MPLP 6-60662 (G25/1). I. Diexallophasis remota Group Mullins, 2001; MPLP 10-60673 (H34). J. Dilatisphaera williereae (Martin, 1966) Lister, 1970; MPLP 2-60704 (Q39/2). K. Dorsennidium europaeum (Stockmans and Willière, 1960) Mullins, 2001; MPLP 7-60736 (L34/4). L. Dorsennidium pertonense (Dorning, 1981) Sarjeant and Stancliffe, 1996; MPLP 7-60736 (U41). M. Duvernaysphaera aranaides (Cramer, 1964a) emend. Cramer and Díez, 1972; MPLP 4-61059 (C47/3). N. cf. Eisenackidium argentinum Pöthe de Baldis, 1997; MPLP 2-61057 (Q42). O. Emphanisporites rotatus (McGregor, 1961) McGregor, 1973; MPLP 4-61059 (W47/2). P, Q. Emphanisporites sp.; MPLP 2-61057 (Q42), MPLP 7-60736 (K43), respectively. R. Estiastra barbata (Downie, 1963) Sarjeant and Stancliffe, 1994; MPLP 8-60677 (X37/3). S. Dactylofusa sp.; MPLP 3-61058 (T35/3). T. Eupoikilofusa cf. stratifera (Cramer, 1964b) Cramer, 1970; MPLP 1-60667 (R48). Scale bars 20 µm.

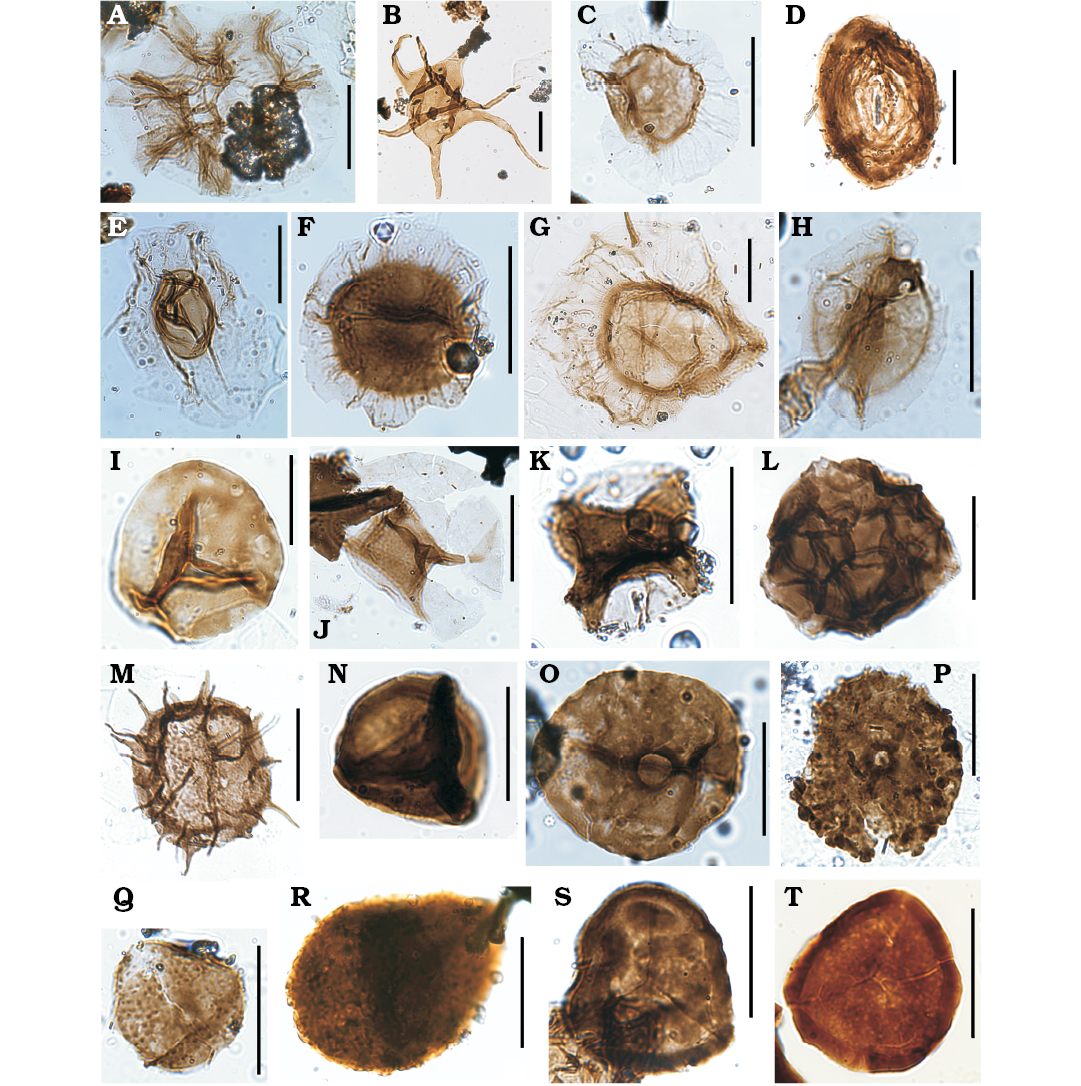

Fig. 8. Palynomorphs from the studied sections of the Los Espejos Formation of Argentina, Cerro La Chilca, Ludfordian (A), Quebrada Ancha, Přídolí (B, G, R, T), Quebrada Ancha, Ludfordian (C, E, F, H–L, N–P, S), Quebrada Ancha, Gorstian?–Ludfordian? (D), Cerro La Chilca, Gorstian?–Ludfordian? (M, Q). A. Eupoikilofusa striatifera (Cramer, 1964b) Cramer, 1970; MPLP 4-61059 (H25). B. Eupoikilofusa cantabrica (Cramer, 1964b) Cramer, 1970; MPLP 9-60664 (U41/1). C. Fimbiaglomerella divisa Loeblich and Drugg, 1968; MPLP 7-60736 (U29/1). D. Gorgonisphaeridium saharicum (Lister, 1964b) Sarjeant and Vavrdová, 1997; MPLP 1-60667 (M47). E. Gorgonisphaeridium sp. A Le Hérissé, 1989; MPLP 2-60704 (O39/1). F. Helios aranaides Cramer, 1964a; MPLP 7-60736 (F28/4). G. Helosphaeridium malvernense Dorning, 1981; MPLP 9-60664 (F27/3). H. Helosphaeridium pseudodictyum Lister, 1970; MPLP 7-60736 (P24). I. Helosphaeridium sp.; MPLP 8-60677 (L51). J. Hoegklintia gogginensis Mullins, 2001; MPLP 4-61059 (G49/3). K. Hoegklintia longispina Pöthe de Baldis, 1998; MPLP 7-60736 (D26/1). L. Leiofusa banderillae Cramer, 1964b; MPLP 7-60736 (G50). M. Leiofusa bernesgae Cramer, 1964b; MPLP 2-61057 (N37/1) N. Leiofusa estrecha Cramer, 1964b; MPLP 8-60677 (N50/2). O. Leiofusa fusiformis (Eisenack, 1934) Eisenack, 1938; MPLP 8-60677 (E40/1). P. Leptobrachion arbusculiferum (Downie, 1963) Dorning, 1981; MPLP 7-60736 (B31/3). Q. Lophosphaeridium magnum Pöthé de Baldis, 1971; MPLP 2-61057 (N31/3). R. Lophosphaeridium cf. microgranulosum Thusu, 1973b; MPLP 10-60673 (V46/3). S. Lophosphaeridium parverarum Stockmans and Willière, 1963; MPLP 3-60659 (W47/3). T. Melikeriopalla polygonia (Staplin, 1961) Mullins, 2001; MPLP 7-60736 (W37/2). Scale bars 20 µm.

Fig. 9. Palynomorphs from the studied sections of the Los Espejos Formation of Argentina, Cerro La Chilca, Homerian? (A, L), Cerro La Chilca, Gorstian?–Ludfordian? (B, I), Cerro La Chilca, Ludfordian (C, H, O, Q, T), Quebrada Ancha, Ludfordian (D–G, J, N, P, R, S), Quebrada Ancha, Přídolí (K, U), Quebrada Ancha, Gorstian?–Ludfordian? (M). A–F. cf. Melikeriopalla sp. A. MPLP 1-61065 (W30/3). B. MPLP 3-61058 (L33). C. MPLP 7-61062 (P43/3). D. MPLP 2-60704 (L26). E. MPLP 3-60659 (F38). F. MPLP 4-62521 (T40/4). G. Multiplicisphaeridium arbusculum forma A of Mullins (2001); MPLP 7-60736 (D30/1). H. Multiplicisphaeridium cladum (Downie, 1963) Eisenack, 1969; MPLP 4-61059 (E50/1). I. Multiplicisphaeridium mingusi Le Hérissé, 1989; MPLP 2-61057 (M31/1). J. Multiplicisphaeridium monki Le Hérissé, 1989; MPLP 3-60659 (O45/2). K. Multiplicisphaeridium rochesterensis Cramer and Diez, 1972; MPLP 9-60664 (U27). L. Nanocyclopia sp.; MPLP 1-61065 (U38/1). M. Neoveryhachium carminae (Cramer, 1964a) Cramer, 1970; MPLP 1-60667 (P45/2). N. Onondagella asymmetrica (Deunff, 1961) Playford, 1977; MPLP 7-60736 (X44). O. cf. Oppilatala frondis (Cramer and Díez, 1972) Dorning, 1981; MPLP 4-61059 (F45). P. Oppilatala grahni Le Hérissé, 1989; MPLP 7-60736 (E38/1). Q. Oppilatala insolita (Cramer and Díez, 1972) Dorning, 1981; MPLP 4-61059 (Q50). R. Oppilatala ramusculosa (Deflandre, 1945) Dorning, 1981; MPLP 7-60736 (N37/4). S. Ozotobrachion palidodigitatus (Cramer, 1966b) Playford, 1977; MPLP 7-60736 (P48/4). T. Percultisphaera incompta Richards and Mullins, 2003; MPLP 4-61059 (W47/4). U. Polyedrixium? cf. embudum Cramer, 1964a; MPLP 9-60664 (D39/1). Scale bars 20 µm.

Fig. 10. Palynomorphs from the studied sections of the Los Espejos Formation of Argentina, Cerro La Chilca, Ludfordian (A, E, G, N), Quebrada Ancha, Ludfordian (B, C, F, H, J, K, M, P, R), Quebrada Ancha, Přídolí (D, O, Q, S), Cerro La Chilca, Homerian? (I), Quebrada Ancha, Gorstian?–Ludfordian? (L), Cerro La Chilca, Gorstian?–Ludfordian? (T). A. Polyedryxium wenlockium (Dorning, 1981) Le Hérissé, 1989; MPLP 4-61059 (G33). B. Polygonium sp.; MPLP 7-60736 (E30/1). C. Pterospermella bernardinae (Cramer, 1964a) Eisenack, Cramer, and Díez, 1973; MPLP 7-60736 (F28/4). D. cf. Pterospermella circumstriata (Jardiné, Combaz, Magloire, Penguel, and Vachey, 1972) Eisenack, Cramer, and Díez, 1973; MPLP 9-60664 (U47). E. Pterospermella elliptica Pöthe de Baldis, 1981; MPLP 4-61059 (D46/2). F. Pterospermella (Pterospermopsis) marysae Le Hérissé, 1989; MPLP 8-60677 (V50/4). G. Pterospermella martinii (Cramer, 1966b) Eisenack, Cramer, and Díez, 1973; MPLP 4-61059 (S41/4). H. Pterospermella cf. pertonensis (Dorning, 1981) Mullins, 2001; MPLP 7-60736 (O36/1). I. Punctatisporites sp.; MPLP 1-61065 (F44/1). J. Quadraditum fantasticum Cramer, 1964a; MPLP 7-60736 (F29/3). K. Quadraditum incisum Cramer, 1964a; MPLP 4-62521 (F42/1). L. cf. Rugosphaera tuscarorensis Strother and Traverse, 1979; MPLP 1-60667 (U47/2). M. Salopidium granuliferum (Downie, 1959) Mullins, 2001; MPLP 2-60704 (G44/3). N. Tetrahedraletes medinensis (Strother and Traverse, 1979) Wellman and Richardson, 1993; MPLP 6-61061 (G48/1). O. Schismatosphaeridium longhopense Dorning, 1981; MPLP 9-60664 (N39). P. Schismatosphaeridium cf. rugulosum (Dorning, 1981) Mullins, 2001; MPLP 2-60704 (O30/1). Q. Schismatosphaeridium sp. B Le Hériseé, 1989; MPLP 11-61020 (J35/2). R. cf. Segestrespora membranifera (Johnson, 1985) Burgess, 1991; MPLP 6-60662 (V40). S. Synorisporites verrucatus Richardson and Lister, 1969; MPLP 9-60664 (R33). T. Vermiverruspora rumneyi (Burgess and Richardson, 1995) Beck and Strother, 2001; MPLP 2-61057 (V34). Scale bars 20 µm.

Fig. 11. Palynomorphs from the studied sections of the Los Espejos Formation of Argentina, Quebrada Ancha, Přídolí (A, F, K, M, N), Cerro La Chilca, Gorstian?–Ludfordian? (B, L), Quebrada Ancha, Ludfordian (C, E, H), Cerro La Chilca, Ludfordian (D, G, I, J). A. Tylotopalla caelamenicutis Loeblich, 1970; MPLP 14-60982 (E32/3). B. Tylotopalla deerlijkianum (Martin, 1973) Martin, 1978; MPLP 2-61057 (K42/2). C. Tylotopalla robustispinosa (Downie, 1959) Mullins, 2001; MPLP 2-60704 (L42/2). D. Veryhachium trispinosum Group Servais, Vecoli, Li, Molyneux, Raevskaya, and Rubinstein, 2007; MPLP 4-61059 (E33). E. Vestitusdyadus sp.; MPLP 8-60677 (G31/1). F. Villosacapsula setosapellicula (Loeblich, 1970) Loeblich and Tappan, 1976; MPLP 9-60664 (Q30). G. Villosacapsula sp.; MPLP 5-61060 (U32/2). H. Visbysphaera cf. pirifera (Eisenack, 1954) Kiryanov, 1978; MPLP 8-60677 (T33). I. Indeterminate palynomorphs; MPLP 4-61059 (G35/4) (I1, I2 are different focus). J. cf. Veryhachium sp., with abnormal processes, distally expanded; MPLP 4-61059 (P25/3). K–N. Emphanisporites? tenuis sp. nov. K. MPLP 13-60984 (N30/2). L. MPLP 2-61057 (Q42). M. MPLP 10-60673 (J23). N. MPLP 12-60986 (R34). Scale bars 20 µm.

Discussion

Phytoplankton is sensitive to external factors such as light, salinity, temperature and terrestrial nutrient inputs. Therefore, variations in its diversity and abundance are supposed to reflect changes in the depositional environment (e.g., Al-Ameri 1983; Richardson and Rasul 1990; Le Hérissé 2002; Rubinstein and García Muro 2011; García Muro et al. 2016). The abundance of miospores in marine deposits reflects environmental conditions favourable for the development of plant producers as well as the proximity to the shoreline (e.g., Al-Ameri 1983; Traverse 2007).

Diversity.—The lower part of the Quebrada Ancha section (Fig. 3B, C) displays a high diversity of marine and terrestrial palynomorphs and yields almost twice the number of species than the Cerro La Chilca section (Fig. 2) despite the fact that both sections would be coeval (García Muro and Rubinstein 2015). Such variations could be related to their different positions within the basin since Quebrada Ancha is located at its southern part. From palaeocurrent analyses, a general deepening trend towards the south of the basin was observed (Astini and Maretto 1996). Therefore, the more distal environment towards the south could have created conditions under which the phytoplankton diversity was higher (e.g., Dorning 1981; Li et al. 2004). Furthermore, the preservation of the palynomorphs and the organic matter, in general, is better in distal environments than in nearshore environments due to less destructive taphonomic processes (Versteegh and Riboulleau 2010 and references therein). On the other hand, the base of the Los Espejos Formation, in the Cerro La Chilca section, is unexposed. Also, as evidenced by the intercalation of sandstone beds, the studied part of Cerro La Chilca represents more proximal facies than those of the lower part in the Quebrada Ancha section, therefore possibly preventing the preservation of the palynomorphs.

A total of 105 species of phytoplankton and 43 species of miospores were recorded from the Los Espejos Formation, considering the palynomorphs from Río de Las Chacritas (Rubinstein and García Muro 2011) and Río Jáchal (García Muro et al. 2014a) as well as from the Quebrada Ancha (García Muro et al. 2014b and this contribution) and the Cerro La Chilca (this contribution) sections (Fig. 1). Even though it cannot be ensured that both levels are equivalent, the palynomorph assemblages from sample MPLP 4-61059 of the Cerro La Chilca section and sample MPLP 7-60736 of the Quebrada Ancha section, both of which were dated as Ludfordian based on palynomorphs (García Muro and Rubinstein 2015), are highly diversified as regards phytoplankton and present a better preservation than other assemblages of the unit. A high diversity during the Ludfordian in the Central Precordillera of San Juan was also noticed in a previous study (Rubinstein and García Muro 2013) and local palaeoenvironmental conditions that would have favoured phytoplankton development during this age was thus suggested. According to Le Hérissé (2002), an increase in the diversity of marine palynomorphs could be interpreted as a consequence of more favourable water mass conditions for algal cysts development. Hagström (1997) and Stricanne et al. (2006) recorded abundant, diverse, and exceptionally well-preserved marine and terrestrial palynomorphs from the Ludfordian of Gotland. This was attributed by Stricanne et al. (2006) to humid climatic conditions that trigger an increase in nutrient input to the sea, indicated by low stable isotopic values and named as the late Ludfordian A-period. Further studies need to be carried out in order to understand the global and local environmental conditions and their effects on the phytoplankton and miospore distribution in this part of western Gondwana.

Upwards in the sections, miospore diversity is higher than phytoplankton diversity, thus suggesting a close proximity to land in coincidence with a more proximal environment, which had been previously interpreted based on sedimentological studies (Astini and Maretto 1996). As evidenced in the Quebrada Ancha section, as well as in previous contributions (Rubinstein and García Muro 2013 and references therein; García Muro and Rubinstein 2015 and references therein), palynomorphs completely disappear in the uppermost part of the Los Espejos Formation, probably as a result of coarser sediment deposition in more proximal environment, which is unsuitable for the palynomorph preservation. This part of the section probably span the Silurian/Devonian boundary at the northernmost outcrops of the Los Espejos Formation, as it was palynologically identified for the first time in Precordillera in the northern Río Jáchal section (García Muro et al. 2014a).

Abundance.—The lowest sample from the Cerro La Chilca section yielded a similar abundance of acritarchs, chlorophytes, and miospores, even though this part of the section corresponds to a low-energy open shelf. There is no sedimentological evidence in the bearing level that suggests deposits of shallowing-up sequence. Upwards, in the following four samples, acritarchs, followed by chlorophytes and miospores, display the higher relative abundance. In sample MPLP 6-61061 of Cerro La Chilca, the relative abundance of miospores and chlorophytes increases and is accompanied by a decline in acritarchs (Fig. 2). Acritarch relative abundance continues to decrease toward the uppermost sample, MPLP 7-61062, and reaches its minimum at this level, while miospores reach their maximum relative abundance of this section. The dominance of terrestrial palynomorphs occurs during the late Ludfordian in the Cerro La Chilca section and the Přídolí in the Quebrada Ancha section. Such changes coincide with the recurrence of sandstone beds associated with more proximal facies and terrestrial input. Terrestrial influence normally produces a decrease in salinity, therefore providing a suitable environment for chlorophytes and resulting in their increase in abundance (e.g., Le Hérissé 2002; Rubinstein and García Muro 2011).

Marine palynomorphs exhibit higher relative abundance in almost all the samples of the Quebrada Ancha section except for sample MPLP 6-60662, which displays a higher relative abundance of chlorophytes and miospores. As with sample MPLP 1-61065 from the Cerro La Chilca section, there is no evidence of terrestrial influence in the sedimentary record, which was interpreted to have been deposited in a low energy open shelf (Astini and Maretto 1996). Generally, miospores tend to be more abundant in proximity to the shoreline (e.g., Al-Ameri 1983; Tyson 1993; Batten 1996; Filipiak and Zatoń 2011). The presence of hinterland miospores in distal marine facies could be related to climatic conditions. Specifically, their small size together with the early Palaeozoic atmospheric-environmental conditions would have contributed to their transport into the basin by wind and water (Al Ameri 1983; Stricanne et al. 2006; Wellman et al. 2013; Hagström 1997 and references therein; Traverse 2007; García Muro et al. 2014; Mehlqvist et al. 2014). According to Ferrero’s (2006) geochemical analyses, there are small shallowing-up cycles, of 4th and 5th order, in the lower and middle part of the Los Espejos Formation, in the Quebrada Ancha locality. These subtle environmental changes, not reflected in the lithology, would have possibly influenced palynomorph relative abundances and therefore resulted in a similar abundance of marine and terrestrial palynomorphs in the same level.

Palaeoenvironmental and palaeogeographic interpretations.—The comparison of the marine phytoplankton taxa from the Los Espejos Formation with coeval assemblages worldwide suggests that marine phytoplankton presents a wide distribution, even across the Rheic Ocean, as already suggested by Rubinstein (1993). In more recent years, different contributions point to a narrow to almost closed Rheic Ocean since the late Silurian that did not constitute an impassable barrier for marine phytoplankton and chitinozoans (e.g., Jaglin and Paris 2002; Le Hérissé 2002; Rubinstein et al. 2008; Breuer et al. 2017) and thus enabled the exchange of species.

As regards trilete spores, the highest percentages of species in common with the Precordillera assemblages correspond to localities from the same Gondwana palaeocontinent, such as North Africa and Brazil (Rubinstein and Steemans 2002; Steemans et al. 2008; Spina and Vecoli 2009), and from peri-Gondwana, such as Spain (e.g., Richardson et al. 2001). Breuer et al. (2017) observed close similarities between Saudi Arabia miospore assemblages of the Přídolí and those from Spain. Even though the geographical position of Armorica is still under discussion (e.g., Torsvik and Cocks 2004), the similarities observed between the assemblages from Armorica (Spain), Saudi Arabia and Argentina would indicate that Armorica (Spain) was possibly located at an intermediate position between the remaining two regions. The similarities between miospore assemblages from different palaeolatitudes in the same continent, such as Tunisia (North Africa), Urubu (Brazil) and Precordillera, denote that the distribution of spores could have been influenced by palaeolatitudes as well as by local environments (Steemans et al. 2007; García Muro et al. 2014b). It should be taken into account that, nowadays, miospore assemblages are still scarce and geographically restricted, which inhibits reliable correlations. On the other hand, plant cryptospore-producers were widely distributed, hence revealing their plasticity in adapting to different climates and environmental conditions and/or their higher dispersal potential (Steemans et al. 2007; García Muro et al. 2016 and references therein).

Sample MPLP 4-61059 of the Cerro La Chilca section contains a remarkable specimen of a possible Veryhachium that presents abnormal processes, distally expanded (Fig. 11J). The presence of teratological specimens with, for instance, deformed or inflated processes could have resulted from perturbations in the environmental conditions such as variations in intensity of light, temperature, and chemistry, as well as volcanic events (Le Hérissé 1989) and sea level fluctuations. The latter would be the case for the Llandovery/Wenlock boundary (Rodrigues and Cardoso 2005). Vandenbroucke et al. (2015) interpreted the malformations of plankton, even if it represents a very small proportion of the assemblage, as induced by the presence of metals (Fe, Mo, Pb, Mn, and As) in the early Palaeozoic and as possible indicators of subsequent mass extinction events. In contrast to what was observed for other palaeoplates such as Baltica and Laurentia (Calner 2005), there is hitherto no evidence of environmental crises and mass extinctions during the late Silurian in neither Precordillera nor Western Gondwana. However, there would be some evidence of Ludfordian Lau Event effects in the peri-Gondwanan Bohemia terrane (Lehnert et al. 2007b) in northern Gondwana, Tunisia (Vecoli et al. 2009), and in East Gondwana, Australia (Talent et al. 1993; Jeppsson et al. 2007). Nevertheless, further studies are needed before confirming the occurrence of such event in the Precordillera Basin.

In the last few years, the knowledge of palynomorphs from Precordillera has much advanced (Rubinstein and García Muro 2011, 2013; García Muro et al. 2014a, b, 2016; García Muro and Rubinstein 2015). Notably, in such contributions, 58 species of phytoplankton and 28 of miospores were recognized for the first time in the Palaeozoic of Argentina. Moreover, 34 species of phytoplankton and one of a trilete spore were recorded for the first time for Gondwana. These findings of marine phytoplankton, previously known from other paleoplates (Avalonia, Baltica, Laurentia), would support their cosmopolitan distribution pattern. In view of the present state of knowledge, further palynological studies on the Silurian of Precordillera are required in order to establish more reliable correlations with other assemblages from Gondwana and other palaeocontinents.

Conclusions

Marine palynomorphs are predominant in almost all of the studied samples from the Los Espejos Formation. Terrestrial palynomorphs tend to be more abundant in the upper part of the sections, which is consistent with the transition, from base to top, of an open shelf to a nearshore environment.

A relatively high diversity of organic-walled phytoplankton and miospores was recorded. The highest diversified and better preserved marine phytoplankton, probably related to more favourable environmental conditions, comes from levels dated as Ludfordian in both studied sections. However, more studies are needed to evaluate the influence of the local environment on the diversity and abundance of phytoplankton.

Based on regional and inter-continental correlations, the phytoplankton evidences a wide palaeogeographic distribution during the late Silurian. The trilete spore assemblages show stronger similarities with those from other Gondwanan and peri-Gondwanan localities, such as Brazil, Tunisia, and Spain, therefore suggesting their more restricted dispersal ability. Moreover, the correlation between trilete spore assemblages from Gondwana, peri-Gondwana, and Armorica may contribute to constrain the palaeogeographical position of Armorica.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ricardo Astini (Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina) for helping with the field work. Marcela Giraldo (Université de Liège, Belgium) is acknowledged for the palynological laboratory processing. We are grateful to Rafael Bottero (IANIGLA) for the hand drawing and Florencia Carotti (Buenos Aires, Argentina) for language and style revision. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestions that improved this paper. Financial support for this study was provided by CONICET (PIP 11220120100364), FONCYT (PICT 2013-2206 and PICT 2015-0473) and CONICET-FNRS Project (Scientific Cooperation Program between Argentina and Belgium).

References

Al-Ameri, T.K. 1983. Acid-resistant microfossils used in the determination of Palaeozoic palaeoenvironments in Libya. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 44: 103–116. Crossref

Al-Ameri, T.K. 1984. New taxa of the acritarch group “Pterospermopsis”. Journal of the Geological Society of Iraq 16: 126–147.

Al-Ameri, T.K. 2010. Palynostratigraphy and the assessment of gas and oil generation and accumulations in the Lower Paleozoic, Western Iraq. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 3: 155–179. Crossref

Astini, R.A. and Maretto, H.M. 1996. Análisis estratigráfico del Silúrico de la Precordillera Central de San Juan y consideraciones sobre la evolución de la cuenca. 2º Congreso de Exploración de Hidrocarburos (Buenos Aires), Actas 1: 351–368.

Astini, R.A., Benedetto, J.L., and Vaccari, N.E. 1995. The early Paleozoic evolution of the Argentine Precordillera as a Laurentian rifted, drifted, and collided terrane: A geodynamic model. Geological Society of America Bulletin 107: 253–273. Crossref

Al-Ruwaili, M.H. 2000. New Silurian acritarchs from the subsurface of northwestern Saudi Arabia. In: S. Al-Hajri and B. Owens (eds.), Stratigraphic Palynology of the Paleozoic of Saudi Arabia. GeoArabia Special Publication 1: 82–91.

Balme, B. 1988. Miospores from Late Devonian (early Frasnian) strata, Carnarvon Basin, Western Australia. Palaeontographica Abteilung B 209: 109–166.

Batten, D.J. 1996. Palynofacies and palaeoenvironmental interpretations. In: J. Jansonius and D.C. McGregor (eds.), Palynology: Principles and Applications, 1011–1064. American Association of Stratigraphic Palynologists Foundation, Salt Lake City.

Beck, J.H. and Strother, P.K. 2001. Silurian spores and cryptospores from the Arisaig group, Nova Scotia, Canada. Palynology 25: 127–177. Crossref

Beck, J.H. and Strother, P.K. 2008. Miospores and cryptospores from the Silurian section at Allenport, Pennsylvania, USA. Journal of Paleontology 82: 857–883. Crossref

Benedetto, J.L. 2010. El continente de Gondwana a través del tiempo. Una introducción a la Geología Histórica. 384 pp. Academia Nacional de Ciencias, Córdoba.

Benedetto, J.L., Peralta, P., and Sánchez, T.M. 1996. Morfología y biometría de las especies de Clarkeia kozlowski (Brachiopoda, Rhynchonellida) en el Silúrico de la Precordillera Argentina. Ameghiniana 33: 279–299.

Benedetto, J.L., Racheboeuf, P.R., Herrera, Z.A., Brussa, E.D., and Toro, B.A. 1992. Brachiopodes et biostratigraphie de la Formation de Los Espejos, Siluro-Dévonien de la Précordillère (NW Argentine). Geobios 25: 599–637. Crossref

Breuer, P., Al-Ghazi, A., Al·Ruwaili, M., Higgs, K.T., Steemans, P., and Wellman, C.H. 2007. Early to Middle Devonian miospores from northern Saudi Arabia. In: F. Paris, B. Owens, and M.A. Miller (eds.), Palaeozoic Palynology of the Arabian Plate and Adjacent Areas. Revue de Micropaléontologie 50: 27–57. Crossref

Breuer, P., Le Hérissé, A., Paris, F., Steemans, P., Verniers, J., and Wellman, C.H. 2017. A distinctive marginal marine palynological assemblage from the Přídolí of northwestern Saudi Arabia. Revue de Micropaléontologie 60: 371–402. Crossref

Brito, I.M. 1967. Silurian and Devonian Acritarcha from Maranhão Basin, Brazil. Micropaleontology 13: 473–482. Crossref

Brito, I.M. and Santos, A.S. 1965a. Contribuiçaõ ao conhecimento dos micrôfósseis Silurianos e Devonianos da Bacia do Maranhão. Parte 1. Os Netromorphitae (Leiofusidae). Divisao de Geologia e Mineralogia, Rio de Janeiro, XIX Congresso Brasileiro de Geologia 40: 57.

Burgess, N.D. 1991. Silurian cryptospores and miospores from the type Llandovery area, south-west Wales. Palaeontology 34: 575–599.

Burgess, N.D. and Richardson, J.B. 1991. Silurian cryptospores and miospores from the type Wenlock area, Shropshire, England. Palaeontology 34: 601–628.

Burgess, N.D. and Richardson, J.B. 1995. Late Wenlock to early Prídolí cryptospores and miospores from south and southwest Wales, Great Britain. Palaeontographica, Abteilung B 236: 1–44.

Calner, M. 2005. Silurian carbonate platforms and extinction events—ecosystem changes exemplified from Gotland, Sweden. Facies 51: 584–591. Crossref

Calner, M. 2008. Silurian global events—at the tipping point of climate change. In: A.M.T. Elewa (ed.), Mass Extinctions, 21–58. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

Cardoso, T.R.M. 2005. Acritarcos do Siluriano da Bacia do Amazonas: bioestratigrafia e geocronologia. Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro 63: 727–759.

Cramer, F.H. 1964a. Microplankton from three Palaeozoic formations in the province of Leon, NW-Spain. Leidse Geologische Mededelingen 30: 253–361.

Cramer, F.H. 1964b. Some acritarchs from the San Pedro Formation (Gedinnien) of the Cantabric Mountains in Spain. Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, de Paléontologie et d’Hydrologie 73: 33–38.

Cramer, F.H. 1966a. Hoegispheres and other microfossils incertae sedis of the San Pedro Formation (Siluro–Devonian boundary) near Valporquero, Léon, NW Spain. Notas y Comunicaciónes Instituto Geológico y Minero de España 86: 75–94.

Cramer, F.H. 1966b. Palynology of Silurian and Devonian rocks in northwest Spain. Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, Boletin 77: 225–286.

Cramer, F.H. 1969. Possible implications for Silurian paleogeography from phytoplancton assemblages of the Rose Hill and Tuscarora formations of Pennsylvania. Journal of Paleontology 43: 485–491.

Cramer, F.H. 1970. Distribution of selected acritarchs. An account of the palynostratigraphy and palaeogeography of selected Silurian acritarch taxa. Revista Española de Micropaleontología. Numero Extraordinario: 1–203.

Cramer, F.H. and Díez, M. del C.R. 1972. North American Silurian palynofacies and their spatial arrangement: acritarchs. Palaeontographica Abteilung B 138: 107–180.

Cramer, F.H. and Díez, M. del C.R. 1976. Acritarchs from the La Vid shales (Emsian to lower Couvinian) at Colle, León, Spain. Palaeontographica Abteilung B 158: 72–103.

Cramer, F.H., Diez, M.D.C., and Cuerda, A.J. 1974. Late Silurian chitinozoans and acritarchs from Cochabamba, Bolivia. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Monatshefte 1974 (1): 1–12.

Cuerda, A.J. 1965. Monograptus leintwardensis var. incipiens Wood en el Silúrico de la Precordillera. Ameghiniana 4: 171–178.

Cuerda, A.J. 1969. Sobre las graptofaunas del Silúrico de San Juan, Argentina. Ameghiniana 6: 223–235.

Deflandre, G. 1945. Microfossiles des calcaires siluriens de la Montagne Noire. Annales de Paléontologie 31: 41–75.

Delabroye, A., Munnecke, A., Vecoli, M., Copper, P., Tribovillard, N., Joachimski, M.M., Desrochers, A., and Servais, T. 2011. Phytoplankton dynamics across the Ordovician/Silurian boundary at low palaeolatitudes: Correlations with carbon isotopic and glacial events. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 312: 79–97. Crossref

De Vernal, A., Larouche, A., and Richard, P.J.H. 1987. Evaluation of palynomorph concentrations: the aliquot and the marker-grain methods yield comparable results? Pollen et Spores 29: 291–303.

Deunff, J. 1954. Sur un microplancton du Dévonien du Canada recélant des types nouveaux d’Hystrichosphaeridés. Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des sciences 239: 1064–1066.

Deunff, J. 1959. Microorganismes planctoniques du primaire Armoricain. I.—Ordovicien du Veryhac’h (presqu’ile de Crozon). Bulletin de la Société géologique et mineralogique de Bretagne, nouvelle sér 2: 1–41.

Deunff, J. 1961. Quelques précisions concernant les Hystrichosphaeridées du Dévonien du Canada. Compte rendu sommaire des séances de la Société Géologique de France 8: 216–218.

Dorning, K.J. 1981. Silurian acritarchs from the type Wenlock and Ludlow of Shropshire, England. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 34: 175–203. Crossref

Downie, C. 1959. Hystrichospheres from the Silurian Wenlock Shale of England. Palaeontology 2: 56–71.

Downie, C. 1963. “Hystrichospheres” (acritarchs) and spores of the Wenlock Shales (Silurian) of Wenlock, England. Palaeontology 6: 625–652.

Eisenack, A. 1934. Neue Mikrofossilien des baltischen Silurs III und neue Mikrofossilien des böhmischen Silurs I. Palaeontologische Zeitschrift 16: 52–76. Crossref

Eisenack, A. 1938. Hystrichosphaerideen und verwandte Formen im baltischen Silur. Zeitschrift für Geschiebeforschungen und Flachlandsgeologie 14: 1–30.

Eisenack, A. 1954. Hystrichosphären aus dem baltischen Gotlandium. Senckenbergiana Lethaea 34: 205–211.

Eisenack, A. 1955. Chitinozoen, Hystrichosphären und andere Mikrofossilien aus dem Beyrichia-Kalk. Senckenbergiana Lethaea 36: 157–188.

Eisenack, A. 1969. Zur Systematik einiger paláozoischer Hystrichosphären (Acritarcha) des baltischen Gebietes. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 133: 245–266.

Eisenack, A., Cramer, F.H., and Díez, M. del C.R. 1973. Katalog der fossilen Dinoflagellaten, Hystrichosphären und verwandten Mikröfossilien. Band III Acritarcha 1. Teil. 1104 pp. E. Schweizerbart’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart.

Ferrero, J. 2006. Cicloestratigrafía del Silúro-Devónico de la Precordillera Central (San Juan) a partir de la utilización de parámetros Quimio estratigráficos. 156 pp. Unpublished Thesis, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales, Departamento de Geología Aplicada, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Córdoba.

Filipiak, P. and Zatoń, M. 2011. Plant and animal cuticle remains from the Lower Devonian of southern Poland and their palaeoenvironmental significance. Lethaia 44: 397–409. Crossref

García Muro, V.J. and Rubinstein, C.V. 2015. New biostratigraphic proposal for the Lower Palaeozoic Tucunuco Group (San Juan Precordillera, Argentina) based on marine and terrestrial palynomorphs. Ameghiniana 52: 265–285. Crossref

García Muro, V.J., Rubinstein, C.V., and Martínez, M.A. 2016. Palynology and palynofacies analysis of a Silurian (Llandovery–Wenlock) marine succession from the Precordillera of western Argentina: palaeobiogeographical and palaeoenvironmental significance. Marine Micropaleontology 126: 50–64. Crossref

García Muro, V.J., Rubinstein, C.V., and Steemans, P. 2014a. Palynological record of the Silurian/Devonian boundary in the Argentine Precordillera, western Gondwana. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 274: 25–42. Crossref

García Muro, V.J., Rubinstein, C.V., and Steemans, P. 2014b. Upper Silurian miospores from the Precordillera Argentina: biostratigraphic, palaeonvironmental and palaeogeographic implications. Geological Magazine 151: 472–490. Crossref

Hagström, J. 1997. Land-derived palynomorphs from the Silurian of Gotland, Sweden. GFF 119: 301–316. Crossref

Hünicken, M.A. and Sarmiento, G.N. 1988. Conodontes Ludlovianos de la Formación Los Espejos, Talacasto, provincia de San Juan, R. Argentina. 4º Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía (Mendoza), Actas 3: 225–233.

Jaglin, J.C. and Paris, F. 2002. Biostratigraphy, biodiversity and palaeogeography of late Silurian chitinozoans from A1-61 Borehole (north–western Libya). Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 118: 335–358. Crossref

Jardiné, S., Combaz, A., Magloire, L., Peniguel, G., and Vachey, G. 1972. Acritarches du Silurien terminal et du Dévonien du Sahara Algérien. Comptes rendus 7e Congrès international de stratigraphie et de géologie du Carbonifère. Krefeld, August 1971: 295–311.

Jeppsson, L. 1990. An oceanic model for lithological and faunal changes tested on the Silurian record. Journal of the Geological Society 147: 663–674. Crossref

Jeppsson, L., Talent, J.A., Mawson, R., Simpson, A.J., Andrew, A.S., Calner, M., Whitford, D.J., Trotter, J.A., Sandström, O., and Caldon, H.J. 2007. High-resolution Late Silurian correlations between Gotland, Sweden, and the Broken River region, NE Australia: lithologies, conodonts and isotopes. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 245: 115–137. Crossref

Johnson, N.G. 1985. Early Silurian palynomorphs from the Tuscarora Formation in central Pennsylvania and their palaeobotanical and geological significance. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 45: 307–360. Crossref

Kimyai, A.1983. Palaeozoic microphytoplankton from South America. Revista Española de Micropaleontología 15: 415–426.

Kiryanov, V.V. [Kirânov, V.V.] 1978. Akritarhi silura Volyno-Podolii. 116 pp. Akademiâ Nauk Ukrainskoj SSR, Institut Geologičeskih Nauk, Kiev.

Lakova, I. and Göncüoğlu, M.C. 2005. Early Ludlovian (early Late Silurian) palynomorphs from the Palaeozoic of Camdag, NW Anatolia, Turkey. Journal of the Earth Sciences Application and Research Centre of Hacettepe University 26: 61–73.

Le Hérissé, A. 1989. Acritarches et kystes d’algues Prasinophycées du Silurien de Gotland, Suède. Palaeontographia Italica 76: 57–302.

Le Hérissé, A. 2000. Characteristics of the acritarch recovery in the early Silurian of Saudi Arabia. In: S. Al-Hajri and B. Owens (eds), Stratigraphic Palynology of the Palaeozoic of Saudi Arabia. Special GeoArabia Publication 1, 57–81. Gulf PetroLink, Bahrain.

Le Hérissé, A. 2002. Paleoecology, biostratigraphy and biogeoraphy of late Silurian to early Devonian acritarchs and prasinophyceanphycomata in well A1-61, Western Libya, North Africa. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 118: 359–395. Crossref

Le Hérissé, A. and Gourvennec, R. 1995. Biogeography of upper Llandovery and Wenlock acritarchs. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 86: 111–133. Crossref

Le Hérissé, A., Al-Tayyar, H., and Eem, H. van der 1995. Stratigraphic and paleogeographical significance of Silurian acritachs from Saudia Arabia. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 89: 49–74. Crossref

Le Hérissé, A., Gourvennec, R., and Wicander, R. 1997. Biogeography of late Silurian and Devonian acritarchs and prasinophytes. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 98: 105–124. Crossref

Le Hérissé, A., Mullins, G.L., Dorning, K.J., and Wicander, R. 2009. Global patterns of the organic-walled phytoplankton biodiversity during the late Silurian to earliest Devonian. Palynology 33: 25–75. Crossref

Le Hérissé, A., Paris, F., and Steemans, P. 2013. Late Ordovician–earliest Silurian palynomorphs from northern Chad and correlation with contemporaneous deposits of southeastern Libya. Bulletin of Geosciences 88: 483–504. Crossref

Lehnert, O., Eriksson, M.J., Calner, M., Joachimski, M., and Buggisch, W. 2007a. Concurrent sedimentary and isotopic indications for global climatic cooling in the Late Silurian. Acta Palaeontologica Sinica 46: 249–255.

Lehnert, O., Frýda, J., Buggisch, W., Munnecke, A., Nützel, A., Křiž, J., and Manda, S. 2007b. δ13C records across the late Silurian Lau event: new data from middle palaeo-latitudes of northern peri-Gondwana (Prague Basin, Czech Republic). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 245: 227–244. Crossref

Li, J., Servais,T., Yan, K. , and Zhu, H. 2004.Anearshore–offshore trend in the acritarch distribution of the Early–Middle Ordovician of the Yangtze Platform, South China. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 130: 141–161. Crossref

Lister, T.R. 1970. The acritarchs and chitinozoa from the Wenlock and Ludlow Series of the Ludlow and Millchope areas, Shropshire. Palaeontographical Society Monographs, London 1: 1–100.

Loeblich, A.R. Jr. 1970. Morphology, ultrastructure and distribution of Paleozoic acritarchs. Proceedings of the North American Paleontological Convention, Chicago, Part G 2: 705–788.

Loeblich, A.R. Jr. and Drugg, W.S. 1968. New acritarchs from the Early Devonian (Late Gedinnian) Haragan Formation of Oklahoma, U.S.A. Tulane Studies in Geology 6: 129–137.

Loeblich, A.R. Jr. and Tappan, H. 1976. Some new and revised organic-walled phytoplankton microfossil genera. Journal of Paleontology 50: 301–308.

Loeblich, A.R. Jr. and Wicander, R. 1976. Organic-walled microplankton from the Lower Devonian, late Gedinnian Haragan and Bois d’arc formations of Oklahoma, USA. Part I. Palaeontographica Abteilung B 159: 1–39.

Martin, F. 1966. Les Acritarches du sondage de la brasserie Lust, à Kortrijk (Courtrai) (Silurien belge). Bulletin de la Société belge de géologie, de paléontologie et d’hydrologie 74: 354–400.

Martin, F. 1973. Ordovicien supérieur et Silurien inférieur a Deerlijk (Belgique). Institut royal des sciences naturelles de Bélgique, Mémoire 174: 1–71.

Martin, F. 1978. Sur quelques Acritarches Llandoveriens de Cellon (Alpes Carniques Centrales, Autriche). Geologische Bundesanstalt, Verhandlungen 2: 35–42.

Martinez-Macchiavello, J.C. 1968. Quelques Acritarches d’un échantillon du Dévonien Inférieur (Cordobés) de Blanquillo, Départment de Durazno, Uruguay. Revue de micropaléontologie 11: 77–84.

McGregor, D.C. 1961. Spores with proximal radial pattern from the Devonian of Canada. Geological Survey of Canada Bulletin 76: 1–11. Crossref

McGregor, D.C. and Camfield, M. 1976. Upper Silurian? to Middle Devonian spores of the Moose River basin, Ontario. Geological Survey of Canada Bulletin 263: 1–63. Crossref

Mehlqvist, K., Larsson, K., and Vajda, V. 2014. Linking upper Silurian terrestrial and marine successions. Palynological study from Skåne, Sweden. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 202: 1–14. Crossref

Mehlqvist, K., Vajda, V., and Steemans, P. 2012. Early land plant spore assemblages from the Late Silurian of Skåne, Sweden. GFF 134: 133–144. Crossref

Miller, M.A., Playford, G., and Le Hérissé, A. 1997. Clypeolus,a new acritarch genus from the Ordovician and Silurian. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 98: 95–103. Crossref

Mullins, G.L. 2001. Acritarchs and prasinophyte algae of the Elton Group, Ludlow Series, of the type area. Monograph of the Palaeontographical Society 155: 1–154.

Mullins, G.L. 2004. Microplankton biostratigraphy of the Bringewood Group, Ludlow Series, Silurian, of the type area. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 2: 163–205. Crossref

Munnecke, A., Calner, M., and Harper, D.A. 2010. How does sea level correlate with sea-water chemistry? A progress report from the Ordovician and Silurian. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 296: 213–216. Crossref

Munnecke, A., Samtleben, C., and Bickert, T. 2003. The Ireviken Event in the lower Silurian of Gotland, Sweden—relation to similar Palaeozoic and Proterozoic events. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 195: 99–124. Crossref

Naumova, S.N. 1953. Spore-pollen assemblages of the Upper Devonian of the Russian Platform and their stratigraphic value [in Russian]. Akademiâ nauk SSSR, Geologičeskij institut (Geologičeskiâ seriâ) 60: 1–154.

Playford, G. 1977. Lower to Middle Devonian acritarchs of the Moose River Basin, Ontario. Geological Survey of Canada, Bulletin 279: 1–87. Crossref

Porębska, E., Kozłowska-Dawidziuk, A., and Masiak, M. 2004. The lundgreni event in the Silurian of the East European Platform, Poland. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 213: 271–294. Crossref

Pöthe de Baldis, E.D. 1971. Microplancton del Silurico superior de la Provincia de Santiago del Estero, Republica Argentina. Ameghiniana 8: 282–290.

Pöthe de Baldis, E.D. 1974a. Microplancton adicional del Silúrico Superior de Santiago del Estero, República Argentina. Ameghiniana 4: 313–327.

Pöthe de Baldis, E.D. 1974b. Microplancton de la Formación Los Espejos, Provincia de San Juan, República Argentina. Revista Española de Micropaleontología 7: 507–518.

Pöthe de Baldis, E.D. 1977. Paleomicroplancton adicional del Devonico inferior de Uruguay. Revista española de micropaleontologia 9: 235–250.

Pöthe de Baldis, E.D. 1981. Paleomicroplancton y mioesporas del Ludloviano Inferior de la Formación Los Espejos en el perfil Los Azulejitos, en la Provincia de San Juan, República Argentina. Revista Española de Micropaleontología 13: 231–265.

Pöthe de Baldis, E.D. 1998. Acritarcas de la Formación Los Espejos (Silúrico superior) del perfil Aguadas de los Azulejitos, San Juan, Argentina. Revista Española de Micropaleontología 30: 1–18.

Racheboeuf, P.R., Casier, J.G., Plusquellec, Y., Toro, M., Mendoza, D., Pires de Carvalho, M. da G., Le Hérissé, A., Paris, F., Fernández-Martínez, E., Tourneur, F., Broutin, J., Crasquin, S., and Janvier, P. 2012. New data on the Silurian–Devonian palaeontology and biostratigraphy of Bolivia. Bulletin of Geosciences 87: 269–314. Crossref

Richards, R.E. and Mullins, G.L. 2003. Upper Silurian microplankton of the Leinwardine Group, Ludlow Series, in the type Ludlow area and adjacent regions. Palaeontology 46: 557–611. Crossref

Richardson, J.B. and Ioannides, N.S. 1979. Emphanispoirites splendens, a new name for Emphanisporites pseudoerraticus Richardson & Ioannides, 1973 (preoccupied). Micropaleontology 25: 111. Crossref

Richardson, J.B. and Ioannides, N. 1973. Silurian palynomorphs from the Tanezzuft and Acacus Formations, Tripolitania, North Africa. Micropaleontology 19: 257–307. Crossref

Richardson, J.B. and Lister, T.R. 1969. Upper Silurian and Lower Devonian spore assemblages from the Welsh Borderland and south Wales. Palaeontology 12: 201–252.

Richardson, J.B. and Rasul, S.M. 1990. Palynofacies in a Late Silurian regressive sequence in the Welsh Borderland and Wales. Journal of the Geological Society 147: 675–686. Crossref

Richardson, J.B., Rasul, S.M., and Al-Ameri, T. 1981. Acritarchs, miospores and correlation of the Ludlovian–Downtonian and Silurian–Devonian boundaries. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 34: 209–224. Crossref

Richardson, J.B., Rodríguez, R.M., and Sutherland, S.J.E. 2001. Palynological zonation of Mid-Palaeozoic sequences from the Cantabrian Mountains, NW Spain: implications for inter-regional and interfacies correlation of the Ludford/Prídolí and Silurian/Devonian boundaries, and plant dispersal patterns. Bulletin of the Natural History Museum, Geology 57: 115–62.

Rickards, R.B., Brussa, E.D., Toro, B., and Ortega, G. 1996. Ordovician and Silurian graptolite assemblages from Cerro del Fuerte, San Juan Province, Argentina. Geological Journal 31: 101–122. Crossref

Rodrigues, M.A.C. and Cardoso, T.R.M. 2005. Acritarcos anormais: um caso teratológico no limite Llandovery/Wenlock na Bacia do Amazonas, Brasil. Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro 63: 385–393.

Rodríguez González, R.M. 1978. Mioesporas de la Formación San Pedro/Furada (Silúrico Superior–Devónico Inferior), Cordillera Cantábrica, NO de España. Palinologia, Número Extraordinario 1: 407–433.

Rodríguez González, R.M. 1983. Palinología de las formaciones del Silúrico Superior–Devónico Inferior de la Cordillera Cantábrica, noroeste de España. 231 pp. Thesis Universidad de León, León.

Rubinstein, C.V. 1992a. Palinología del Silúrico Superior (Formación Los Espejos) de la Quebrada de Las Aguaditas, Precordillera de San Juan, Argentina. Ameghiniana 29: 231–248.

Rubinstein, C.V. 1992b. Palinología del Silúrico superior (Formación Los Espejos) de Loma de los Piojos, Precordillera de San Juan, Argentina. Ameghiniana 29: 287–303.

Rubinstein, C.V. 1993. Acritarchs from the upper Silurian of San Juan, Argentina: biostratigraphy and paleobiogeography. Special Paper in Palaeontology 48: 67–78.

Rubinstein, C.V. 1995. Acritarchs from the upper Silurian of Argentina: their relationship with Gondwana. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 8: 103–115. Crossref

Rubinstein, C.V. and Brussa, E.D. 1999. A palynomorph and graptolite biostratigraphy of the Central Precordillera Silurian basin, Argentina. Bolletino della Società Paleontologica Italiana 38: 257–266.

Rubinstein, C.V. and García Muro, V.J. 2011. Fitoplancton marino de pared orgánica y mioesporas silúricos de la Formación Los Espejos, en el perfil del Río de Las Chacritas, Precordillera de San Juan, Argentina. Ameghiniana 48: 618–641. Crossref

Rubinstein, C.V. and García Muro, V.J. 2013. Silurian to Early Devonian organic-walled phytoplankton and miospores from Argentina: biostratigraphy and diversity trends. Geological Journal 48: 270–283. Crossref

Rubinstein, C.V. and Steemans, P. 2002. Miospore assemblages from the Silurian–Devonian boundary, in borehole A1-61, Ghadamis Basin, Libya. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 118: 397–421. Crossref

Rubinstein, C.V., Le Hérissé, A., and Steemans, P. 2008. Lochkovian (Early Devonian) acritarchs and prasinophytes from the Solimões Basin, northwestern Brazil. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 249: 167–184. Crossref

Sánchez, T.M., Waisfeld, B.G., and Benedetto, J.L. 1991. Lithofacies, taphonomy, and brachiopod assemblages in the Silurian of western Argentina: a review of Malvinokaffric realm communities. Journal of South America Earth Sciences 4: 307–329. Crossref

Sánchez, M.T., Waisfeld, B.G., and Toro, B.A. 1995. Silurian and Devonian molluscan bivalves from Precordillera Region, Western Argentina. Journal of Palaeontology 69: 869–886. Crossref

Sarjeant, W.A.S. and Stancliffe, R.P.W. 1994. The Micrhystridium and Veryhachium complexes (Acritarcha: Acanthomorphitae and Polygonomorphitae): a taxonomic reconsideration. Micropaleontology 40: 1–77. Crossref

Sarjeant, W.A.S. and Stancliffe, R.P.W. 1996. The acritarch genus Polygonium, Vavrdová emend Sarjeant and Stancliffe 1994: a reassessment of its constituent species. Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique 117: 355–369.

Sarjeant, W.A.S. and Vavrdová, M. 1997. Taxonomic reconsideration of Multiplicisphaeridium Staplin, 1961 and other acritarch genera with branching processes. Geolines 5: 1–52.

Schultz, G. 1967. Mikrofossilien des oberen Llandovery von Dalarne (Schweden). Kölner Geologische Hefte 13: 175–187.

Servais, T., Vecoli, M., Li, J., Molyneux, S.G., Raevskaya, E.G., and Rubinstein, C.V. 2007. The acritarch genus Veryhachium Deunff 1954: taxonomic evaluation and first appearance. Palynology 31: 191–203. Crossref

Spina, A. and Vecoli, M. 2009. Palynostratigraphy and vegetational changes in the Siluro-Devonian of the Ghadamis Basin, North Africa. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 282: 1–18. Crossref

Staplin, F.L. 1961. Reef-controlled distribution of Devonian microplankton in Alberta. Palaeontology 4: 392–424.

Steemans, P. 1989. Palépgeographiede l’éodevonien ardennais et des regions limitrophes. Annales de la Société Géologique de Belgique 112: 103–119.

Steemans, P., Higgs, K.T., and Wellman, C.H. 2000. Cryptospores and trilete spores from the Llandovery, Nuayyim-2 Borehole, Saudi Arabia. In: S. Al-Hajri and B. Owens (eds.), Stratigraphic Palynology of the Palaeozoic of Saudi Arabia, Special GeoArabia Publication 1, 92–115. Gulf PetroLink, Bahrain.

Steemans, P., Le Hérissé, A., and Bozdogan, N. 1996. Ordovician and Silurian cryptospores and miospores from southeastern Turkey. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 93: 35–76. Crossref

Steemans, P., Rubinstein, C.V., and de Melo, J.H.G. 2008. Siluro-Devonian miospore biostratigraphy of the Urubu River area, western Amazon Basin, northern Brazil. Geobios 41: 263–282. Crossref

Steemans, P., Wellman, C.H., and Filatoff, J. 2007. Palaeophytogeographical and palaeoecological implications of a miospore assemblage of earliest Devonian (Lochkovian) age from Saudi Arabia. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 250: 237–254. Crossref

Stockmans, F. and Willière, Y. 1960. Hystrichosphères du Dévonien belge (Sondage de l’Asile d’aliénés à Tournai). Senckenbergiana Lethaea 41: 1–11.

Stockmans, F. and Willière, Y. 1963. Les Hystrichosphères ou mieux les Acritarches du Silurien Belge. Sondage de la Brasserie Lust à Courtrai (Kortrijk). Bulletin de la Société belge de Géologie, de Paléontologie et d’Hydrologie 71: 450–481.

Stricanne, L., Munnecke, A., and Pross, J. 2006. Assessing mechanisms of environmental change: Palynological signals across the Late Ludlow (Silurian) positive isotope excursion (δ13C, δ18O) on Gotland, Sweden. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 230: 1–31. Crossref

Stricanne, L., Munnecke, A., Pross, J., and Servais, T. 2004. Acritarch distribution along an inshore-offshore transect in the Gorstian (lower Ludlow) of Gotland, Sweden. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 130: 195–216. Crossref

Strother, P.K and Traverse, A. 1979. Plant microfossils from the Llandoverian and Wenlock rocks of Pennsylvania. Palynology 3: 1–21. Crossref

Talent, J.A., Mawson, R., Andrew, A.S., Hamilton, P.J., and Whitford, D.J. 1993. Middle Palaeozoic extinction events: faunal and isotopic data. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 104: 139–152. Crossref

Tappan, H. and Loeblich, A.R. Jr. 1971. Surface sculpture of the wall in Lower Paleozoic acritarchs. Micropaleontology 17: 385–410. Crossref

Tchibrikova, E.V. [Čibrikova, E.V.] 1959. Spory iz devonskih i bolee drevnih otloženii Baškirii. 247 pp. Akademiâ Nauk SSSR, Moskva.