Evidence for parallel development of ever-growing molars in Early Pleistocene rodents from southern Spain and their paleoenvironmental implications

JORDI AGUST� and PEDRO PINERO

Agust�, J. and Pinero, P. 2023. Evidence for parallel development of ever-growing molars in Early Pleistocene rodents from southern Spain and their paleoenvironmental implications. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 68 (2): 379�391.

In this paper, we present a detailed survey on the rodent fauna from the site of Barranco de los Conejos (Guadix-Baza Basin, southern Spain). Its rodent fauna is composed of three arvicolines (Orcemys giberti, Manchenomys oswaldoreigi, and Tibericola vandermeuleni) and two murids (Castillomys rivas and Apodemus atavus). The three arvicoline species present ever-growing molars. Orcemys giberti and Manchenomys oswaldoreigi can be considered as descendants of local Mimomys species (Mimomys medasensis and Mimomys tornensis, respectively), while Tibericola vandermeuleni is an eastern inmigrant. Loosening of roots in Orcemys giberti and Manchenomys oswaldoreigi is explained as an adaptation to a fossorial way of life, in relation to the Early Pleistocene glacial�interglacial dynamics, which led to cooler and drier conditions. This environmental change would also explain the dispersal of Tibericola from the eastern Mediterranean.

Key words: Mammalia, Rodentia, Muridae, Arvicolinae, Early Pleistocene, Guadix-Baza Basin, Spain.

Jordi Agust� [jordi.agusti@icrea.cat; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7240-1992 ], ICREA, Instituci� Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avan�ats, Pg. Llu�s Companys 23, 08010 Barcelona, Spain; IPHES-CERCA, Institut Catala de Paleoecologia Humana i Evoluci� Social, Zona Educacional 4, Campus Sescelades URV (Edifici W3), 43007 Tarragona, Spain; Area de Prehistoria, Universitat Rovira i Virgili (URV), Avinguda de Catalunya 35, 43002 Tarragona, Spain.

Pedro Pinero [ppinero@iphes.cat; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5626-2777 ], IPHES-CERCA, Institut Catala de Paleoecologia Humana i Evoluci� Social, Zona Educacional 4, Campus Sescelades URV (Edifici W3), 43007 Tarra�gona, Spain; Area de Prehistoria, Universitat Rovira i Virgili (URV), Avinguda de Catalunya 35, 43002 Tarragona, Spain.

Received 4 April 2023, accepted 16 May 2023, available online 19 June 2023.

Copyright � 2023 J. Agust� and P. Pinero. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (for details please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The Early Pleistocene at 1.8 Ma is a key period in the evolution of the mammalian faunas in western Eurasia. At this time, strong glacial pulses forced by obliquity are recorded in the marine record for mid latitudes, coinciding with the onset of the Walker circulation at lower latitudes (Burckle 1995). This is also a time of significant dispersal events among mammalian faunas, such as the first record of Eastern ovibovine bovids of the genera Praeovibos and Soergelia (Agust� et al. 2013). Almost coincident with this event took place the first hominin dispersal out of Africa to Eurasia, as recorded at Dmanisi site in Georgia at 1.8�Ma ago (Vekua et al. 2002; Lordkipanidze et al. 2007). Among the small mammals, the most significant event is the widespread dispersal in the Northern Hemisphere from east to west of the first arhizodont arvicoline rodents of the Allophaiomys (Allophaiomys deucalion, Allophaiomys pliocaenicus; Meulen 1973; Agust� 1991; Garapich and Nada�chowski 1996). As a difference with the arvicoline rodents of the genus Mimomys, roots never appear, so the molars are ever growing. Development of ever-�growing molars in this group has been interpreted as a response to a diet based on hard items, such as grasses. In this way, the dispersal of Allophaiomys has been interpreted as a result of the expansion of cold steppic conditions throughout Eurasia. However, this scenario has been challenged by the evidence recorded at the site of Barranco de los Conejos in the Guadix-Baza Basin. This site presents a peculiar arvicoline association, composed of three different arhizodont species, none of them referable to Allophaiomys: Orcemys giberti, Manchenomys oswaldoreigi, and Tibericola vandermeuleni. Orcemys giberti was originally described by Martin et al. (2018) from the sites of Barranco de los Conejos (type locality) and Barranco del Paso, both in the Guadix-Baza Basin. In this paper we have enlarged the lectotype of this species with new material, including m1, m3, and M2. Manchenomys oswaldoreigi was described for the first time in Barranco de los Conejos. Tibericola vandermeuleni was originally described as a new species of Allophaiomys by Agust� (1991), based on nine m1 and one M3. In this paper, we have enlarged considerably the sample of this species, including four M3 and 14 complete m1, which provide a more complete overview of its variability. Finally, the murids Apodemus atavus and Castillomys rivas from Barranco de los Conejos are described for the first time in this paper.

Institutional abbreviations.�IPHES, Institut Catala de Paleo�ecologia Humana i Evoluci� Social, Tarragona, Spain.

Other abbreviations.�A, anteroconid complex length; AC, anteroconid cap; AL, anterior lobe; B, shortest distance between BRA3 and LRA4; BRA, buccal re-entrant angle; BSA, buccal salient angle; C, shortest distance between LRA3 and BRA3; L, length; LRA, lingual re-entrant angle; LSA, lingual salient angle; M, upper molar; m, lower molar; pac1, posterior accessory cuspid; PC, posterior cap; T1�T7, triangles 1�7; t1�t12, tubercles 1�12; W, width.

Geological setting

The Barranco de los Conejos site is placed in the Guadix-Baza Basin, in southern Spain (Granada province; Agust� et al. 2013). This basin records a very complete continental succession ranging from the Late Miocene to the Middle Pleistocene (H�sing et al. 2010; Agust� et al. 2015b; Pinero et al. 2018a). The paleontological record includes more than 60 fossiliferous levels, among them the sites of Barranco Le�n and Fuente Nueva 3, which record the oldest evidence of hominin presence in Western Europe at 1.2�1.4�Ma (Toro-Moyano et al. 2013; Agust� et al. 2015a). As these sites, Barranco de los Conejos is included in the Upper Member of the Baza Formation (Oms et al. 2000; Agust� et al. 2013). Previous lithostratigraphic and magnetostratigraphic analyses have shown that Barranco de los Conejos is placed at the base of the upper Matuyama geomagnetic chron (Agust� et al. 2013). From a biostratigraphic point of view, this site occupies an intermediate position between the earliest Pleistocene pre-Olduvai level of Galera 2 and the Early Pleistocene post-Olduvai site of Venta Micena (Oms et al. 2000, 2011; Agust� et al. 2011). Provided that the age of Venta Micena has been estimated between 1.6�1.4 Ma (Duval et al. 2011; Agust� et al. 2015b), the age of Barranco de los Conejos can be estimated at about 1.8 Ma, roughly coeval with the Dmanisi site in Georgia.

Material and methods

The fossil material referred to here was collected from the Barranco de los Conejos site during several sampling campaigns, as it is also the case of the arvicoline material included in this paper (Mimomys sp., Mimomys medasensis). All the sediment retrieved during these campaigns was water-screened using superimposed 4-, 1-, and 0.5-mm mesh sieves. The rodent collection from Barranco de los Conejos includes 76 rodent teeth, corresponding to five different species. These fossils are housed at the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES-CERCA; Tarragona, Spain). All the measurements are expressed in millimetres and were taken with the software DinoCapture 2.0, using photographs from the Digital Microscope AM4115TL Dino-Lite Edge. Rodent teeth are illustrated by means of micrographs taken with Environmental Scanning Electron Microscopy (ESEM) at the Servei de Recursos Cient�fics i Tecnics de la Universitat Rovira i Virgili (Tarragona, Spain).

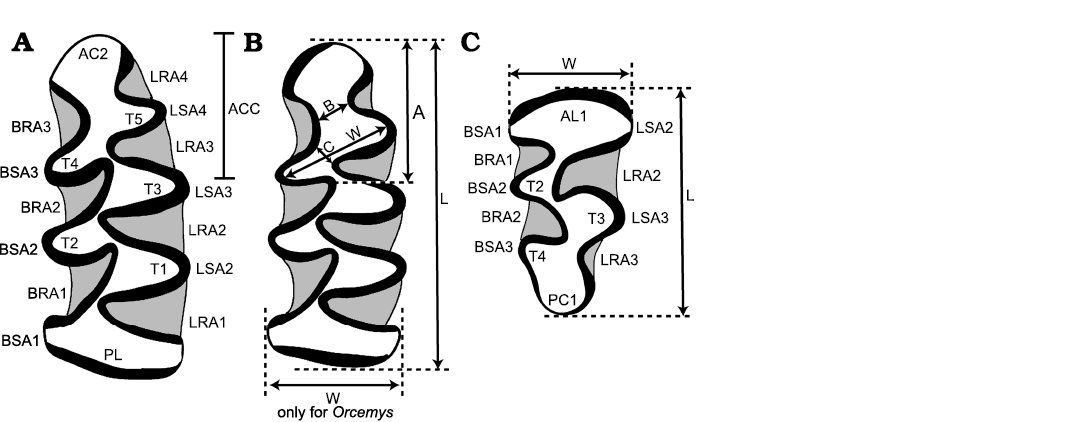

The terminology and measuring methods employed in the descriptions of the arvicoline teeth (only m1 and M3 have been considered in the case of Manchenomys oswaldoreigi and Tibericola vandermeuleni) are those of Meulen (1973), modified by Rabeder (1981) for Orcemys giberti (Fig. 1). Weerd (1976) was followed when we describe murid teeth, and length and width have been measured as defined by Mart�n-Su�rez and Freudenthal (1993).

Fig. 1. Nomenclature and measurements of arvicoline molars. A, B. Left m1 of Manchenomys (nomenclature (A) and measurements (B). C. Right M3 of Manchenomys. Abbreviations: A, ACC length; AC2, anteroconid cap; AL1, anterior lobe; B, shortest distance between BRA3 and LRA4; BRA, buccal re-entrant angle; BSA, buccal salient angle; C, shortest distance between LRA3 and BRA3; L, occlusal surface length; LRA, lingual re-entrant angle; LSA, lingual salient angle; PC, posterior cap; PL, posterior lobe; T1�T7, triangles 1�7; W, width.

Systematic palaeontology

Order Rodentia Bowdich, 1821

Family Cricetidae Fischer, 1817

Subfamily Arvicolinae Gray, 1821

Genus Orcemys Martin, Tesakov, Agust�, and Johnston, 2018

Type species: Orcemys giberti Martin, Tesakov, Agust�, and Johnston, 2018, Lower Pleistocene, Barranco de los Conejos.

Orcemys giberti Martin, Tesakov, Agust�, and Johnston, 2018

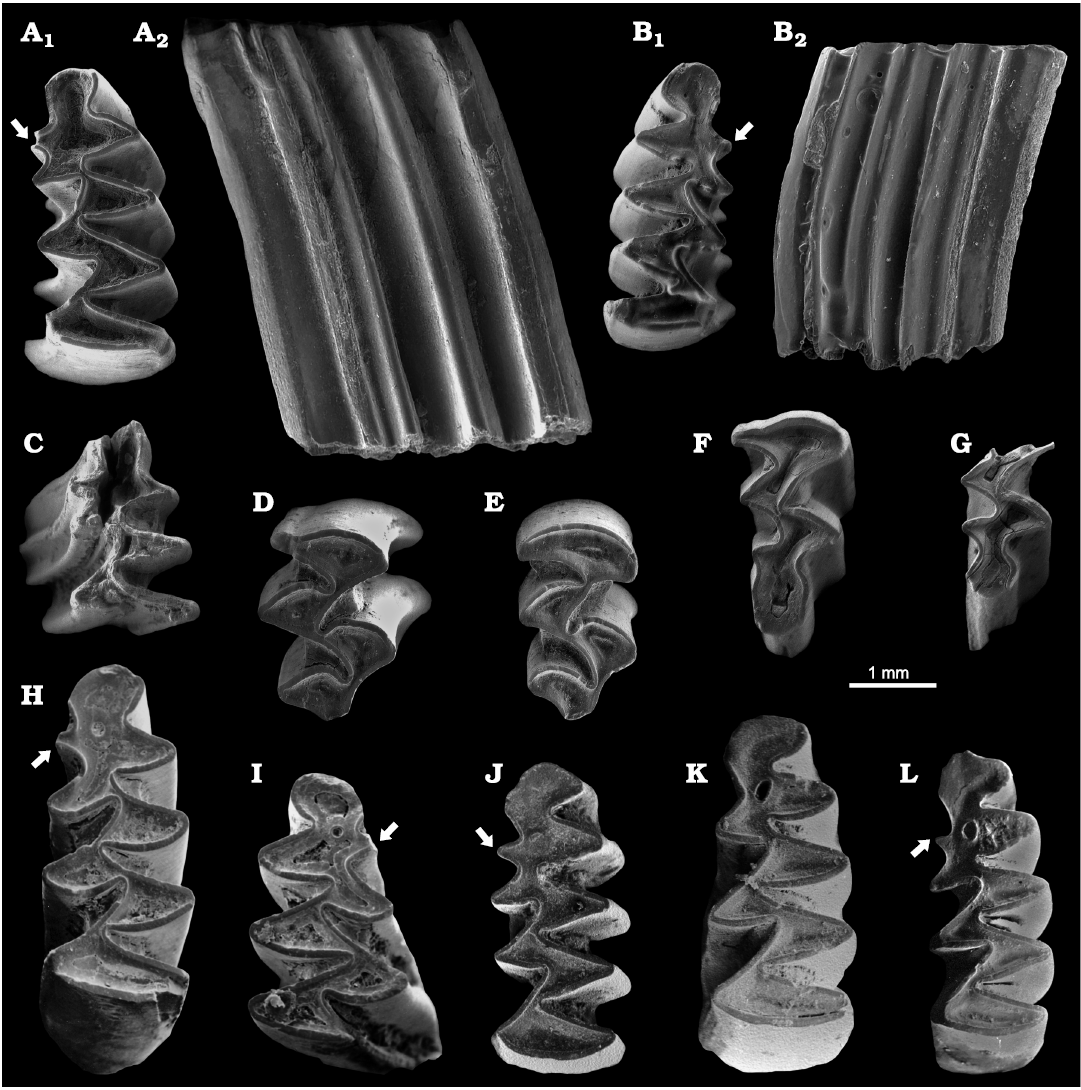

Fig. 2A�G.

Material.�Two M2 (IPHES-BC-32, 117), two M3 (IPHES- BC-119, posterior fragment; IPHES-BC-120), and four m1 (IPHES-BC-30, holotype; IPHES-BC-31, anterior fragment; IPHES-BC-113, anterior fragment; IPHES-BC-118). All from Lower Pleistocene, Barranco de los Conejos, Guadix-Baza Basin, Spain.

Measurements.�See Table 1.

Table 1. Measurements (in mm) of the teeth of Orcemys giberti from Barranco de los Conejos (this work); m1 of Mimomys sp. from Cortijo de Don Alfonso, Cementerio de Orce, and Fuentecica 5 (this paper); and m1 of Mimomys medasensis from Galera 1G (this work) and Almenara-Casablanca 1 (Esteban Aenlle and L�pez Mart�nez 1987). N, number of specimens.

|

Locality |

Species |

Element |

Length |

Width |

||||||

|

N |

min |

mean |

max |

N |

min |

mean |

max |

|||

|

Barranco de los Conejos |

Orcemys giberti |

M2 |

2 |

2.44 |

2.44 |

2.44 |

2 |

1.46 |

1.47 |

1.47 |

|

M3 |

1 |

� |

1.74 |

� |

1 |

� |

1.40 |

� |

||

|

m1 |

2 |

3.40 |

3.46 |

3.51 |

2 |

1.38 |

1.45 |

1.52 |

||

|

Cortijo de Don Alfonso |

Mimomys sp. |

m1 |

1 |

� |

3.93 |

� |

1 |

� |

1.71 |

� |

|

Cementerio de Orce |

Mimomys sp. |

m1 |

1 |

� |

3.88 |

� |

1 |

� |

1.64 |

� |

|

Fuentecica 5 |

Mimomys sp. |

m1 |

3 |

3.54 |

3.63 |

3.67 |

3 |

1.45 |

1.57 |

1.64 |

|

Galera 1G |

Mimomys medasensis |

m1 |

1 |

� |

3.70 |

� |

1 |

� |

1.55 |

� |

|

Almenara-Casablanca 1 |

Mimomys medasensis |

m1 |

37 |

2.80 |

3.42 |

3.95 |

37 |

1.10 |

1.43 |

1.75 |

Description.�The m1 has a very simple pattern, composed of an anteroconid cap (AC2), five alternating triangles (T1, T2, T3, T4 and T5) and a posterior lobe. A thin deposit of cement can be recognized at the labial ends of the re-entrant angles. The AC2 is widely confluent with the T4 and T5, both triangles being also widely confluent. A prominent mimomyan ridge is always present, being the only mimomyan feature that can be recognized, with no evidence of enamel islet. The anterior wall of the AC2 is free-enameled as it is the case of the labial wall of the mimomyan ridge, characterized by high dentine tract. The connection between the T4 and the T3 is very straight, as it is the connection between the T3 and the T2. In contrast, the T2 and T1 are widely confluent. The connection between the T1 and the posterior lobe is again very straight.

The M2 has an occlusal pattern composed of an anterior lobe (AL1) and three alternating triangles (T2, T3, T4). The three triangles are disconnected, with no dentine connection between them.

The M3 shows a simple occlusal pattern, with an anterior lobe, two triangles (T2 and T3), and a rounded, elongated posterior cap. The anterior lobe is widely confluent with the T2, while the connection between the T2 and T1 is very straight. In contrast, the T1 is again widely confluent with the posterior cap. In the posterior cap, a very shallow BRA3 and a small LRA3 can be recognized.

Fig. 2. ESEM images (all in occlusal view, except A2, B2, C) of Early Pleistocene arvicolines from Spain. A�G. Orcemys giberti Martin, Tesakov, Agust�, and Johnston, 2018, from Barranco de los Conejos, Guadix-Baza Basin. A. Left m1 in occlusal (A1) and lateral (A2) views, holotype, IPHES-BC-30. B. Right m1 in occlusal (B1) and lateral (B2) views, IPHESA-BC-118. C. Right m1 in basal view, IPHES-BC-31. D. Right M2, IPHES-BC-32. E. Right M2, IPHES-BC-117. F. Right M3, IPHES-BC-120. G. Posterior fragment of right M3, IPHES-BC-119. H. Mimomys sp. from Cortijo de Don Alfonso, Guadix-Baza Basin; left m1, IPHES-CDA-01. I. Mimomys sp. from Cementerio de Orce, Guadix-Baza Basin; anterior fragment of right m1, IPHES-CO-B-01. J�L. Mimomys medasensis Michaux, 1971, from Almenara-Casablanca 1, eastern Spain. J. Left m1, IPHESA-ACB-1-CS-4. K. Left m1, IPHESA-ACB-1-CS-3. L. Left m1, IPHESA-ACB-1-CS-5. The white arrows indicate the mimomyan ridge.

Remarks.�The genus and species Orcemys giberti were established by Martin et al. (2018) on the basis of material coming from Barranco de los Conejos (type locality) and Barranco del Paso, both at the Baza Formation of the Guadix-Baza Basin. Previous papers assigned this large arvicoline to Mimomys sp. (Agust� et al. 2013). The original sample consisted in one m1 and one M3 from Barranco de los Conejos (holotype and paratype, respectively), five m1 (four of them broken or eroded), two broken m2, two broken m3, one broken M1/2, and two M3 from Barranco del Paso. Here we add new specimens from Barranco de los Conejos, which shed new light on the variability and phylogenetic relationships of this taxon. The morphology of the m1 occlusal surface led Martin et al. (2018) to raise the question as to whether this species could be included in the lagurine genus Borsodia. However, in the same paper this assignment was discarded since the Barranco de los Conejos teeth still retained a rest of cement in the re-entrant angles. Instead, Agust� et al. (2013) suggested that the new taxon could be an in situ descendant of Mimomys medasensis (Fig. 2J�L), a hypothesis supported by the cladistic analysis presented in Martin et al. (2018). Described for the first time at the site of Islas Medas (NE Spain; Michaux 1971), Mimomys medasensis is a widely distributed species in the Iberian Plio-Pleistocene (Mein et al. 1978; Esteban Aenlle and L�pez-Mart�nez 1987; Sevilla et al. 1991; Agust� et al. 2011; L�pez-Garc�a et al. 2023). An increase in size and hypsodonty has been observed in this species through time (Chaline 1987; Sevilla et al. 1991). In contrast, the presence of this species in the Guadix-Baza Basin is scarce (Agust� et al. 2015b), restricted to the earliest Pleistocene of the Galera section (level Galera 1G; Agust� et al. 1997). In size, Mimomys medasensis is comparable to Orcemys giberti (see Table�1) although it differs because of the development of roots. However, some levels stratigraphically close to Barranco de los Conejos (Cortijo de Don Alfonso, Orce 2, Cementerio de Orce, Fuentecica 5; Agust� et al. 1987; Oms et al. 2000) present an advanced species of arvicoline whose characters are intermediate between the two species. No formal description has been done of these specimens (see Fig. 2H, I), which in previous faunal lists were quoted either as Mimomys ostramosensis or Mimomys cf. ostramosensis (Agust� 1986; Agust� et al. 1987; Oms et al. 2000). This unnamed species is larger and more hypsodont than Mimomys medasensis, comparable in this way to Mimomys ostramosensis. It is characterized by the persistence of mimomyan elements, such as a prominent Mimomys-ridge (like Orcemys giberti) and a residual enamel islet (which is already lost in Orcemys). The persistence of this latter feature in Mimomys sp. explains the huge dentine area between the AC2, T4 and T5 in O. giberti. However, it differs from Orcemys since it still bears roots. Therefore, a continuous lineage could be recognized in the Guadix-Baza Basin from Mimomys medasensis to Orcemys giberti throughout intermediate Mimomys sp. from Cortijo de D. Alfonso, Orce 2, Cementerio de Orce and Fuentecica 5.

Stratigraphic and geographic range.�Lower Pleistocene (Agust� et al. 2013); Barranco de los Conejos and Barranco del Paso, both in the Guadiz-Baza Basin, Spain (Martin et al. 2018).

Genus Manchenomys Agust�, Pinero, Lozano-Fern�ndez, and Jim�nez-Arenas, 2022

Type species: Manchenomys orcensis Agust�, Pinero, Lozano-Fern�ndez, and Jim�nez-Arenas, 2022, Fuente Nueva 3, Lower Pleistocene.

Manchenomys oswaldoreigi (Agust�, Castillo, and Galobart, 1993)

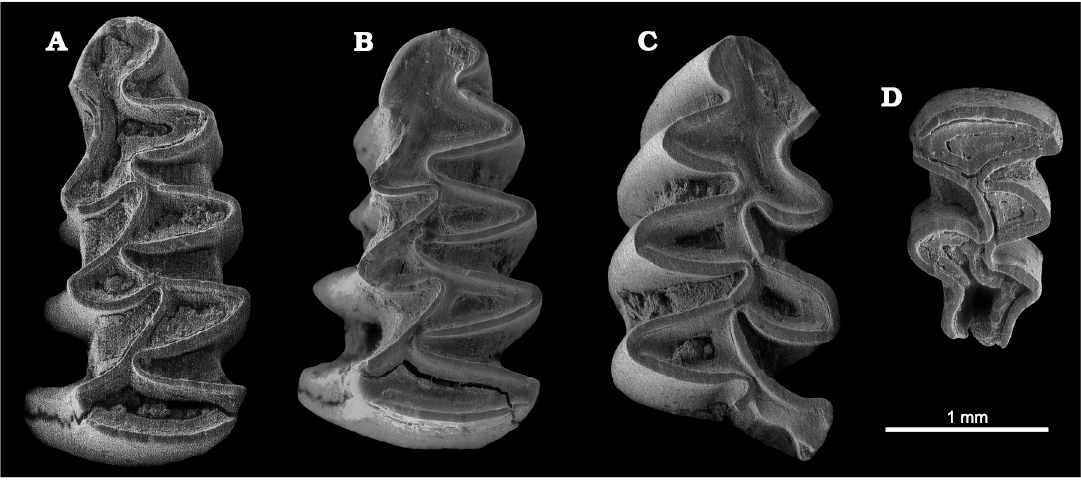

Fig. 3.

Material.�One M3 (IPHES-BC-146), four m1 (IPHES-BC- 28, 33; IPHES-BC-38, anterior fragment; IPHES-BC-112, anterior fragment). All from Lower Pleisto�cene, Barranco de los Conejos, Guadix-Baza Basin, Spain.

Measurements.�See Tables 2, 3.

Table 2. Measurements (in mm) of the m1 of Manchenomys oswaldoreigi from Barranco de los Conejos (this work), and Gilena 2 (Agust� et al. 1993); and Manchenomys orcensis from Fuente Nueva 3 (level Fuente Nueva 3�5), and Quibas Cueva 4�5 (Agust� et al. 2023). N, number of specimens.

|

Locality |

Species |

Length |

Width |

||||||

|

N |

min |

mean |

max |

N |

min |

mean |

max |

||

|

Barranco de los Conejos |

Manchenomys oswaldoreigi |

3 |

2.53 |

2.75 |

2.89 |

4 |

0.89 |

0.96 |

1.03 |

|

Gilena 2 |

11 |

2.61 |

2.71 |

2.82 |

11 |

0.88 |

0.95 |

1.10 |

|

|

Fuente Nueva 3�5 |

Manchenomys orcensis |

16 |

2.81 |

3.00 |

3.23 |

16 |

0.99 |

1.11 |

1.23 |

|

Quibas Cueva 4�5 |

12 |

2.58 |

2.87 |

3.57 |

12 |

1.03 |

1.12 |

1.24 |

|

Table 3. Measurements (in mm) of the M3 of Manchenomys oswaldoreigi from Barranco de los Conejos (this work); and Manchenomys orcensis from Fuente Nueva 3 (level Fuente Nueva 3�5), and Quibas Cueva 4-5 (Agust� et al. 2023). N, number of specimens.

|

Locality |

Species |

Length |

Width |

||||||

|

N |

min |

mean |

max |

N |

min |

mean |

max |

||

|

Barranco de los Conejos |

Manchenomys oswaldoreigi |

1 |

� |

1.62 |

� |

1 |

� |

1.00 |

� |

|

Fuente Nueva 3�5 |

Manchenomys orcensis |

4 |

1.75 |

1.90 |

1.99 |

4 |

0.90 |

0.98 |

1.06 |

|

Quibas Cueva 4�5 |

10 |

1.76 |

1.93 |

2.12 |

10 |

0.85 |

0.99 |

1.07 |

|

Description.�The occlusal pattern of the m1 is composed of an anteroconid cap (AC2), five alternating triangles (T1, T2, T3, T4, and T5) and a posterior lobe. Cement is present in all the re-entrant angles. In all the three specimens the anteroconid is short and asymmetrical, the lingual wall being wider than the labial one. Enamel is always lacking in the anterior half of the wall of the anteroconid complex. The triangles are also asymmetrical, the lingual ones (T1, T3, T5) being wider than the labial ones (T2, T4). Specimens show undifferentiated or slightly negative enamel. LRA4 and BRA3 are not so deep, AC2 and the T4�T5 dentine fields being widely confluent. The T4 and T5 are alternating, being also widely confluent. Dentine channels between the posterior lobe, T1, T2, T3 and T4 are very narrow.

The occlusal pattern of the only M3 is composed of a transverse anterior lobe, two alternating triangles (T2�T3) and a posterior cap (PC1). The anterior lobe, T2 and T3 are isolated, with no dentine channels. The T3 is widely confluent with the PC1. The PC1 is simple and rounded. A small T4 is recognized on the lingual wall of the PC1.

Fig. 3. ESEM images (all in occlusal view) of Manchenomys oswaldoreigi (Agust�, Castillo, and Galobart, 1993), from Lower Pleistocene, Barranco de los Conejos, Guadix-Baza Basin, Spain. A. Left m1, IPHES-BC-28. B. Left m1, IPHES-BC-33. C. Right m1 (the posterior lobe is missing), IPHES-BC-38. D. Left M3, IPHES-BC-145.

Remarks.�The species Manchenomys oswaldoreigi was initially assigned to the genus Mimomys, on the basis of the extended development of roots in the m3 (Agust� et al. 1993). Later it was included in the new genus Manchenomys, established on the basis of the species Manchenomys orcensis from different levels at the late Early Pleistocene sites of Fuente Nueva 3 (type locality, Guadix-Baza Basin) and Quibas (Agust� et al. 2022b). The teeth from Barranco de los Conejos coincides both in size and shape with Manchenomys oswaldoreigi from its type locality, Gilena 2 (Tables 2 and�3), being smaller than the younger Manchenomys orcensis. The values of the indexes A/L and B/W are also comparable to those of Manchenomys oswaldoreigi from Gilena 2, but also to those of Manchenomys orcensis from Fuente Nueva�3 and Quibas (Table 4). In contrast, the values of C/W in Manchenomys oswaldoreigi from Barranco de los Conejos are remarkably low, even when compared with the type species at Gilena 2, which may be an indication of a more archaic population.

Stratigraphic and geographic range.�Lower Pleistocene; Gilena 2 (type locality), Barranco de los Conejos, Cortes de Baza 1, and Fuentecica 5, southern Spain (Agust� et al. 1993, 2022b).

Table 4. A/L, B/W and C/W indexes for the m1 of Manchenomys oswaldoreigi (Barranco de los Conejos and Gilena 2; this work and Agust� et al. 1993), Manchenomys orcensis (Fuente Nueva 3 and Quibas; Agust� et al. 2022a), Allophaiomys deucalion (Villany 5; Meulen 1974), and Allophaiomys pliocaenicus (Betfia 2; Meulen 1974). N, number of specimens.

|

Locality |

N |

A/L |

B/W |

C/W |

||||||||

|

min |

mean |

max |

N |

min |

mean |

max |

N |

min |

mean |

max |

||

|

Barranco de los Conejos |

3 |

39.4 |

40.9 |

42.7 |

4 |

16.9 |

31.4 |

37.9 |

3 |

12.8 |

17.4 |

21.1 |

|

Gilena 2 |

11 |

36.1 |

38.5 |

40.9 |

11 |

29.0 |

35.2 |

43.0 |

11 |

15.5 |

22.6 |

30.0 |

|

Fuente Nueva 3�5 |

16 |

31.9 |

36.6 |

42.7 |

16 |

17.7 |

29.1 |

48.1 |

16 |

14.3 |

22.3 |

27.0 |

|

Quibas-Cueva 4�5 |

12 |

29.9 |

34.4 |

42.6 |

12 |

22.3 |

29.3 |

39.3 |

12 |

15.6 |

22.6 |

31.5 |

|

Villany 5 |

16 |

35.0 |

39.0 |

43.0 |

16 |

30.0 |

36.0 |

50.0 |

16 |

15.0 |

24.0 |

34.0 |

|

Betfia 2 |

96 |

40.0 |

43.0 |

48.0 |

96 |

8.0 |

25.0 |

35.0 |

96 |

15.0 |

24.0 |

30.0 |

Genus Tibericola Koenigswald, Fejfar, and Tchernov, 1992

Type species: Tibericola jordanica (Haas, 1966), Ubeidiya, Lower Pleistocene.

Tibericola vandermeuleni (Agust�, 1992)

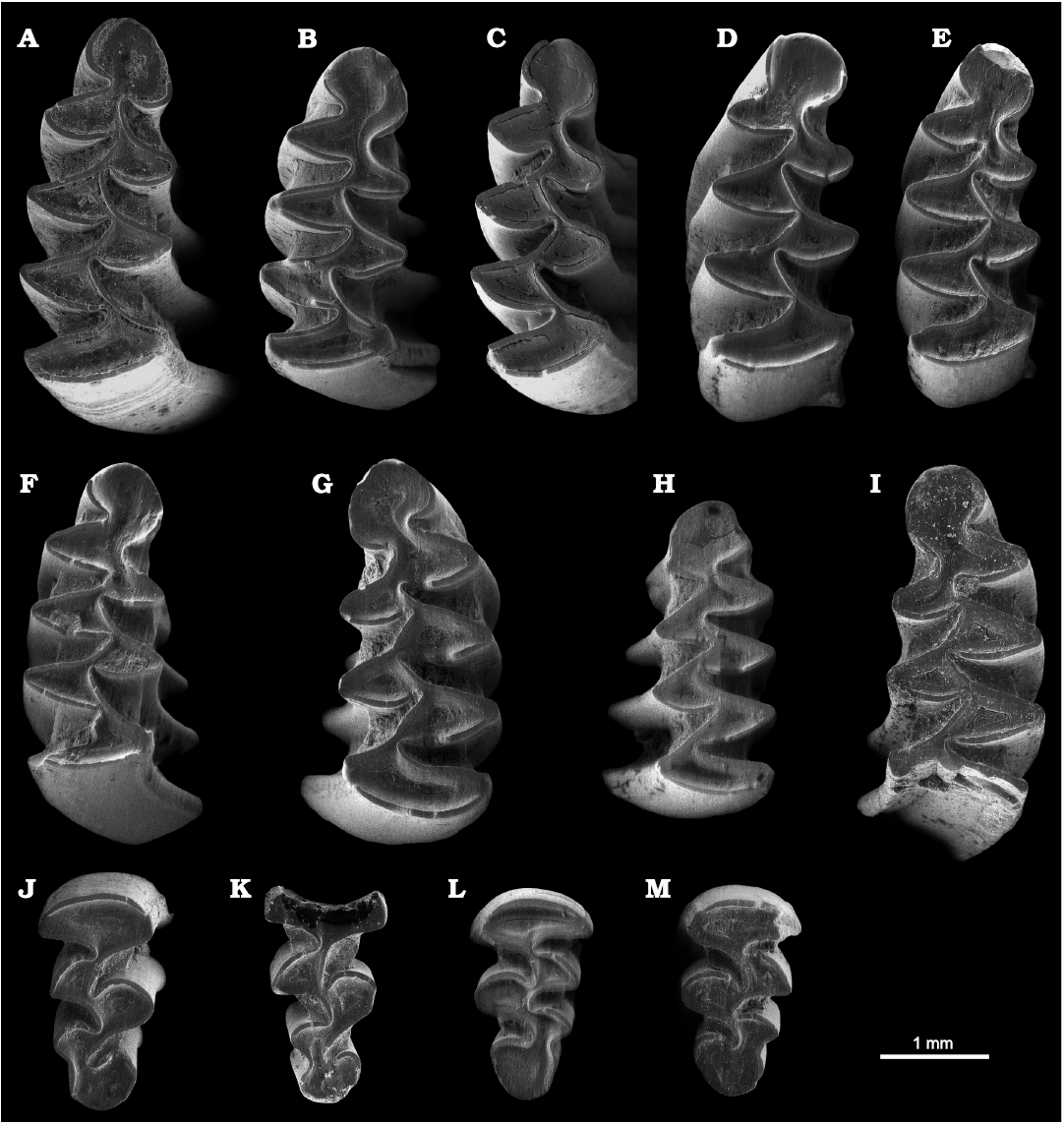

Fig. 4.

Studied material.�Four M3 (IPHES-BC-121, 140�142), and 14 m1 (IPHES-BC-26, anterior fragment; IPHES-BC-27, anterior fragment; IPHES-BC-29, 34; IPHES-BC-35, anterior fragment; IPHES-BC-36, holotype; IPHES-BC-37, anterior fragment; IPHES-BC-39, anterior fragment; IPHES-BC-40, 114�116, 135; IPHES-BC-136, anterior fragment). All from Lower Pleistocene, Barranco de los Conejos, Guadix-Baza Basin, Spain.

Measurements.�See Table 5.

Table 5. Measurements (in mm) of the teeth of Tibericola vandermeuleni from Barranco de los Conejos. N, number of specimens.

|

Element |

Length |

Width |

||||||

|

N |

min |

mean |

max |

N |

min |

mean |

max |

|

|

m1 |

9 |

2.89 |

3.20 |

3.53 |

15 |

1.00 |

1.16 |

1.24 |

|

M3 |

4 |

1.93 |

2.04 |

2.16 |

4 |

1.07 |

1.11 |

1.16 |

Table 6. A/L, B/W, and C/W indexes for the m1 of Tibericola vandermeuleni from Barranco de los Conejos. N, number of specimens.

|

A/L |

B/W |

C/W |

|||||||||

|

N |

min |

mean |

max |

N |

min. |

mean |

max |

N |

min |

mean |

max |

|

8 |

34.5 |

40.8 |

44.4 |

14 |

9.3 |

20.4 |

29.9 |

8 |

2.3 |

8.0 |

11.7 |

Description.�In the m1, the occlusal pattern is composed of an anteroconid cap (AC2), five alternating triangles (T1�T5) and a posterior lobe. All the re-entrant angles are filled by abundant cement. There is a rounded, well-developed anteroconid cap. In four specimens the labial wall outlines a tiny BSA4. In a young individual, this BSA4 is fully developed, as it is a prominent LSA5 (Fig.�4). The LRA3 and BRA3 are very deep, so the dentine connection between the T4 and T5 is very straight, almost inexistent in some cases (see B/W values in Table 6). The connection between the AC2 and T5 is relatively wide (see C/W values in Table 6), but in two specimens it is also quite straight. All the specimens show undifferentiated or slightly negative enamel.

In the M3, the occlusal pattern is composed of a transverse anterior lobe (AL1), three alternating triangles (T2, T3 and T4) and a posterior cap (PC1). The re-entrant angles are always filled by abundant cement. The T4 is widely confluent with the PC1. The T4 and T3 can be also confluent. In contrast, the dentine connections between the T3 and T2, and between the T2 and AL1 are very straight. In all the cases, a well-developed LRA3 is present, which in some specimens can be very deep.

Fig. 4. ESEM images (all in occlusal view) of Tibericola vandermeuleni (Agust�, 1992), from Lower Pleistocene, Barranco de los Conejos, Guadix-Baza Basin, Spain. A. Right m1, IPHES-BC-135. B. Right m1, IPHES-BC-34. C. Right m1, holotype, IPHES-BC-36. D. Right m1, IPHES-BC-114. E. Right m1, IPHES-BC-115. F. Right m1, IPHES-BC-116. G. Left m1, IPHES-BC-29. H. Left m1, IPHES-BC-40. I. Left m1 (the posterior lobe is missing), IPHES-BC-136. J. Right M3, IPHES-BC-141. K. Right M3 (part of the posterior lobe is missing), IPHES-BC-142. L. Left M3, IPHES-BC-121. M. Right M3, IPHES-BC-140.

Remarks.�Tibericola vandermeuleni was originally inclu�ded in Allophaiomys by Agust� (1991). Later, the affi�nities with Tibericola jordanica from Ubeidiya (Israel) became evident, particularly because of the very low C/W values, which enabled to differentiate this genus from the several archaic Allophaiomys species (Allophaiomys deucalion, Allophaiomys pliocaenicus, Allophaiomys ruffoi, Allophaiomys chalinei). Tibericola vandermeuleni from Barranco de los Conejos is certainly less derived than Tibericola jordanica, which presents a fully developed BSA3 and an incipient LRA5. This is in accordance for an older age of the site of Barranco de los Conejos with respect to Ubeidiya, a site dated to 1.4 Ma. A third Tibericola species, Tibericola sakaryaensis was described by �nay et al. (2001) from the Early Pleistocene Turkish site of Degirmendere. This species is characterized by higher B/W and C/W indexes and a lower A/L index with respect to Tibericola vandermeuleni, values which are closer to those of archaic Allophaiomys species such as Allophaiomys deucalion. In this way, based on the evolution of Tibericola, a sequence can be established for the Early Pleistocene Mediterranean sites of Degirmendere (Tibericola sakaryaensis), Barranco de los Conejos (Tibericola vandermeuleni) and Ubeidiya (Tibericola jordanica).

Stratigraphic and geographic range.�Lower Pleistocene; Barranco de los Conejos, southern Spain.

Family Muridae Illiger, 1811

Genus Apodemus Kaup, 1826

Type species: Apodemus sylvaticus (Linnaeus, 1758), present.

Apodemus atavus Heller, 1936

Fig. 5A�D.

Material.�Two M1 (IPHES-BC-5, 11), and two m1 (IPHES- BC-6, 13). All from Lower Pleistocene, Barranco de los Conejos, Guadix-Baza Basin, Spain.

Measurements.�See Table 7.

Table 7. Measurements (in mm) of the teeth of Apodemus atavus from Barranco de los Conejos. N, number of specimens.

|

Element |

Length |

Width |

||||||

|

N |

min |

mean |

max |

N |

min |

mean |

max |

|

|

M1 |

2 |

1.82 |

1.96 |

2.10 |

2 |

1.18 |

1.24 |

1.30 |

|

m1 |

2 |

1.72 |

1.86 |

1.99 |

2 |

1.08 |

1.15 |

1.22 |

Description.�In the M1, the t1 is slightly displaced backward with respect to the t2 and t3. The t1 has a posterior spur reaching basally the t4�t5 intersection in one specimen (IPHES-BC-5). The t2�t3 connection is higher than that of t1�t2. The t3 has a short posterior spur directed to the t5�t6 intersection. The t1bis and t2bis are absent. The well-deve�lo�ped, elongated t7 is connected to the t8, and separated from the t4. The t6 and t9 are connected. There is a reduced t12.

The m1 has a large, round tma. It is connected to the intersection of the two anteroconid lobes, forming a funnel in one specimen (IPHES-BC-13). The anteroconid complex is symmetrical. The lingual lobe of the anteroconid is connected to the protoconid�metaconid junction. There is no longitudinal crest. The labial cingulum is well developed. The oval posterior accessory cuspid (pac1) is similar in size to the tma. It is connected to the anterolabial face of the hypoconid. There are up to three additional accessory cuspids. The oval, lingually displaced posterior heel is variable in size.

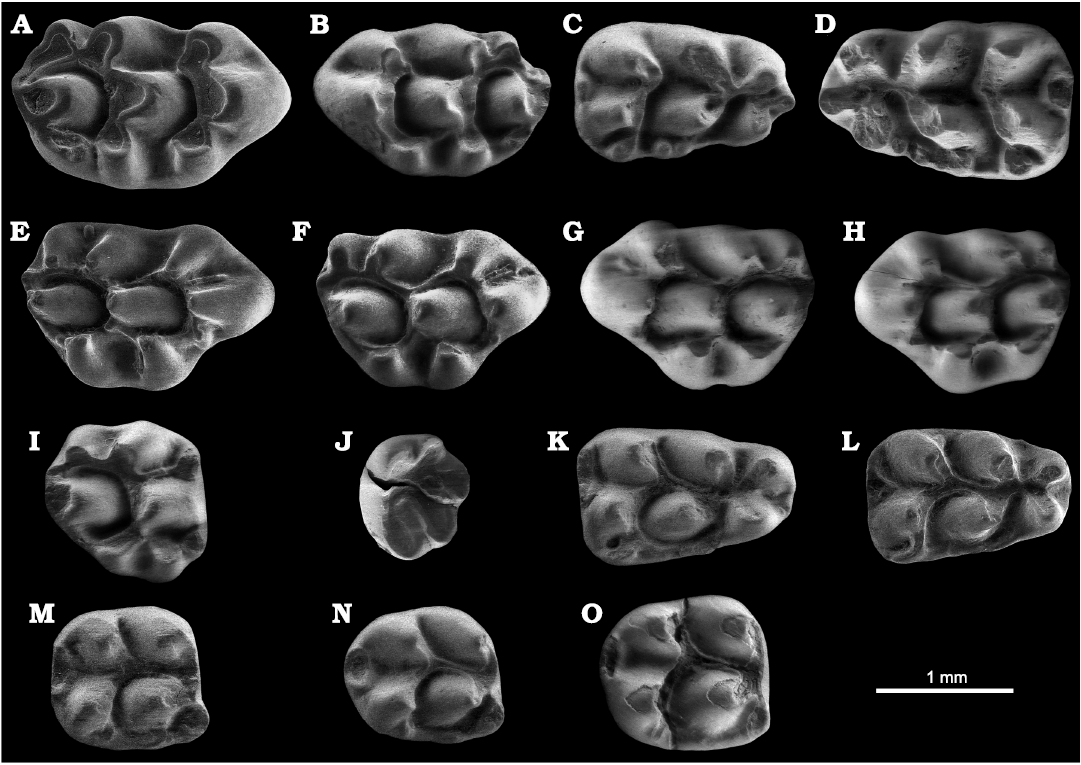

Fig. 5. ESEM images (all in occlusal view) of murids from Lower Pleistocene, Barranco de los Conejos, Guadix-Baza Basin, Spain.. A�D. Apodemus atavus Heller, 1936. A. Right M1, IPHES-BC-11. B. Left M1, IPHES-BC-5. C. Right m1, IPHES-BC-6. D. Left m1, IPHES-BC-13. E�O. Castillomys gracilis Weerd, 1976. E. Right M1, IPHES-BC-1. F. Right M1, IPHES-BC-2. G. Left M1, IPHES-BC-15. H. Left M1, IPHES-BC-16. I. Right M2, IPHES-BC-20. J. Left M3, IPHES-BC-19. K. Left m1, IPHES-BC-7. L. Left m1, IPHES-BC-9. M. Right m2, IPHES-BC-8. N. Right m2, IPHES-BC-10. O. Right m2, IPHES-BC-21.

Remarks.�The presence of t7 and t6�9 connection, the well-developed labial cingulum, and the absence of longitudinal crest in the studied specimens allow their ascription to the genus Apodemus. Apodemus gorafensis, Apodemus jeanteti, and Apodemus agustii are larger than the specimens from Barranco de los Conejos (Michaux 1967; Pasquier 1974; Ruiz Bustos et al. 1984; Mart�n-Su�rez 1988; Bachelet 1990; Pinero et al. 2017; Pinero and Agust� 2019, 2020; L�pez-Garc�a et al. 2023). The studied material is close in size to Apodemus barbarae, but the presence of an individualized t7, and the complete union between the t6 and t9 in the M1 rule out ascription to this species (Weerd 1976). The size is also similar to that of Apodemus gudrunae, but again, the presence of a well-developed t7 precludes assigning the studied sample to this species (see Weerd 1976; Adrover et al. 1993; Pinero et al. 2018b). The small size, the presence of a large tma and the connection between the lingual lobe of the anteroconid and the protoconid�metaconid pair in the m1, and the separation between the t4 and t7 in the M1 are typical traits of Apodemus atavus (see Heller 1936). Furthermore, the material from Barranco de los Conejos is close in size to Apodemus atavus from Tollo de Chiclana 1B (Spain; Minwer-Barakat et al. 2005), Pedrera del Corral d�en Bruach (Spain; L�pez-Garc�a et al. 2023), Asta Regia 3 (Spain; Castillo and Agust� 1996), Moreda 1A, 1B (Spain; Castillo-Ruiz 1990), Alozaina (Spain; Aguilar et al. 1993), Mas Rambault 2, Balaruc 2, Pla de la Ville, Lo Fournas 4 (France; Bachelet 1990), Csarnota (Hungary; Weerd 1976), Monte la Mesa (Italy; Marchetti et al. 2000), Notio 1 (Greece; Hordijk and De Bruijn 2009), Schernfeld (Germany; Pasquier 1974), W�e, R�bielice (Poland; Pas�quier 1974), and Hambach (Germany; M�rs et al. 1998), among other localities. Based on both morphological and biometrical criteria, the specimens from Barranco de los Conejos are attributed to Apodemus atavus.

According to several authors, Apodemus atavus and Apodemus dominans represent extreme phenotypes of a single species, Apodemus dominans being a junior synonym of Apodemus atavus (Fejfar and Storch 1990; Mart�n-Su�rez and Mein 2004; Minwer-Barakat et al. 2005; Garc�a-Alix et al. 2008; Colombero et al. 2014). Some authors considered Apodemus atavus as the direct ancestor of the living Apodemus sylvaticus (Rietschel and Storch 1974; Fejfar and Storch 1990; Mart�n-Su�rez and Mein 1998; Pinero et al. 2022).

Stratigraphic and geographic range.�Uppermost Miocene to Lower Pleistocene (Rietschel and Storch 1974; Fejfar and Storch 1990; Colombero et al. 2014; L�pez-Garc�a et al. 2023; among others). It geographic range includes much of the Palearctic region, from Western Europe to China (Cai and Qiu 1993; Mart�n-Su�rez and Mein 2004; Knitlov� and Hor��ek 2017; Agust� et al. 2022a; among others).

Genus Castillomys Michaux, 1969

Type species: Castillomys crusafonti Michaux, 1969, Layna, Pliocene.

Castillomys rivas Mart�n-Su�rez and Mein, 1991

Fig. 5E�O.

Material.�Eight M1 (IPHES-BC-1, 2; IPHES-BC-3, anterior fragment; IPHES-BC-4, fragmented; IPHES-BC-14�16; IPHES-BC-18, anterior fragment), one M2 (IPHES-BC-20), one M3 (IPHES-BC-19), three m1 (IPHES-BC-7, 9, 12), and four m2 (IPHES-BC-8, 10, 17, 21). All from Lower Plei�stocene, Barranco de los Conejos, Guadix-Baza Basin, Spain.

Measurements.�See Table 8.

Table 8. Measurements (in mm) of the teeth of Castillomys rivas from Barranco de los Conejos. N, number of specimens.

|

Element |

Length |

Width |

||||||

|

N |

min |

mean |

max |

N |

min |

mean |

max |

|

|

M1 |

5 |

1.67 |

1.85 |

1.98 |

8 |

1.22 |

1.26 |

1.30 |

|

M2 |

1 |

� |

1.18 |

� |

1 |

� |

1.16 |

� |

|

M3 |

1 |

� |

0.94 |

� |

1 |

� |

0.89 |

� |

|

m1 |

3 |

1.62 |

1.73 |

1.83 |

3 |

1.04 |

1.05 |

1.06 |

|

m2 |

4 |

1.09 |

1.22 |

1.31 |

4 |

1.05 |

1.10 |

1.14 |

Description.�All the specimens have well-developed longitudinal crests, completing the connection among the tubercles of the crown. The M1 has the t1 displaced backward, and generally develops t1bis and t2bis. The posterior crests of the t1 and t3 are well developed and connected to the t4�t5 and t5�t6 intersections, respectively. There is no t7. The t4�t6, t9, and t8 are connected by a low crest. The t4�t8 crest is also low. The t12 is present as a small bulge between the t8 and t9.

In the M2, the t1 is connected to the t4�t5 intersection by a spur. The t1bis is present as a double t1. The round t3 is connected to the t5�t6 intersection by a narrow, low crest. The t7 is absent. The t4�t6, t9, and t8 are connected. There is a t4�t8 connection. The t12 is shown as a small salient between the t8 and t9.

The M3 has the t1 connected to the t5. The t3 is absent. There is a t4�t6 connection. The t9 is fused to the t8 forming a complex connected to the t6.

In the m1, the tma is absent. The anteroconid complex is slightly asymmetrical. The longitudinal crest is complete, being connected to the lingual part of the protoconid. The metaconid and entoconid are situated slightly anteriorly relative to the protoconid and hypoconid, respectively. The subtriangular or elongated posterior heel reaches the postero-�lingual base of the entoconid. The broad labial cingulum is separated from the protoconid by a valley. The oval or elongated pac1 is connected to the hypoconid by a spur. Another small accessory labial cuspid can be present.

In the m2, the large anterolabial cuspid is connected to the anterior side of the protoconid by a spur. The complete longitudinal crest may be connected to the metaconid�protoconid junction, or to the lingual side of the protoconid. The posterior heel may be oval or elongated. The labial cingulum is well developed and separated from the protoconid by a valley. There is a very small, low pac1 in three out of four specimens. No other accessory cuspids are present.

Remarks.�The small size, the well-developed longitudinal crest on the m1 and m2, the absence of t7, and the presence of a posterior crest on the t1 and t3 in the M1 and M2, are distinguishing features of Castillomys. The material from Barranco de los Conejos can be distinguished from Castillomys gracilis and Castillomys crusafonti by its larger size, and greater development of longitudinal connections both in upper and lower molars (Michaux 1969; Mart�n-Su�rez and Mein 1991). The complete connection among the tubercles of the crown, and the presence of a broad labial cinculum separated from the protoconid by a valley in the m1 and m2 are features present in the species Castillomys rivas. In addition, the specimens from Barranco de los Conejos lie within the size range of Castillomys rivas from its type locality (Loma Quemada-1; Mart�n-Su�rez and Mein 1991). They also agree in size with Castillomys rivas from Pedrera del Corral d�en Bruach (L�pez-Garc�a et al. 2023), Quibas (Pinero et al. 2015, 2022), Valdeganga 7 (Mart�n-Su�rez and Mein 1991), Mas Rambault 2 (Aguilar et al. 2002), Orce 3, Venta Micena 1 (Mart�n-Su�rez 1988), Fuente Nueva 3 (Agust� et al. 2010), and Tollo de Chiclana 10B (Minwer-Barakat et al. 2005), among other localities. Accordingly, the specimens from Barranco de los Conejos are ascribed to Castillomys rivas.

The first appearance of the genus Castillomys presumably coincides with the beginning of the Pliocene (Weerd 1976; Mein et al. 1990; Pinero and Agust� 2019; Pinero et al. 2018a, 2023), whereas it disappeared at the Early�Middle Pleistocene boundary (Agust� et al. 1999). Mart�n-Su�rez and Mein (1991) proposed the anagenetic evolutionary lineage Castillomys gracilis�Castillomys crusafonti�Castillo�mys rivas, which underwent an increase in size and better development of the longitudinal connections along the Pliocene and Early Pleistocene.

Stratigraphic and geographic range.�Early Pleistocene; Iberoccitan province, Spain (Michaux 1969; Mein et al. 1978; Mart�n Su�rez and Mein 1991; Minwer-Barakat et al. 2005; Pinero et al. 2020, 2023; among others). Castillomys rivas has been found in a number of Early Pleistocene localities from Spain and southern France. The oldest populations of Castillomys rivas have been identified in earliest Pleistocene localities, such as Tollo de Chiclana 10 and 10B (MN17; Guadix-Baza Basin, Spain; Minwer-Barakat et al. 2005) and Valdeganga 7 (MN17; Spain; Mein et al. 1978). The youngest record of this species has been reported from the late Early Pleistocene site of C�llar-Baza B (Guadix-Baza Basin, Spain; Agust� et al. 1999).

Discussion

As a difference with other European sequences, in the Lower Pleistocene of southern Spain the first record of arvicolines with ever-growing molars is not represented by species of the genus Allophaiomys, but by three independent lineages, represented by Orcemys, Manchenomys, and Tibericola. While Orcemys and Manchenomys can be rooted in local populations of Mimomys (Mimomys medasensis, Mimomys tornensis; both species present at the site of Almenara-Casablanca�1, in eastern Spain; Agust� et al. 2011; Esteban Aenlle and L�pez-Mart�nez 1987) which developed ever-�growing molars, Tibericola vandermeuleni is an eastern immigrant in the Guadix-Baza Basin. However, these three taxa are almost coeval with the first representatives of Allophaiomys (Allophaiomys deucalion), suggesting that the same environmental constraints that led to the origin of Allophaiomys were also responsible for the loss of roots in Orcemys, Manchenomys, and Tibericola. The causes for this parallel evolution have been a matter of discussion (Agust� et al. 2022b). The evolution towards development of evergrowing, hyperhypsodont molars in large herbivores has been classically explained on the assumption of a grass-based diet (Martin 1984; Janis 1988). However, among voles an alternative explanation has been proposed (Maul et al. 2014; Agust� et al. 2022b), since many representatives of this group display fossorial habits, as an evolutionary response to the glacial�interglacial dynamics. Voles use their incisors to burrow their galleries, so the teeth are exposed to heavy abrasion because of grit (Martin 1993), which at the end led to the development of ever-growing molars.

In any case, the evolution towards developing ever-growing molars is indicative of an environmental change that forced this trend in the Early Pleistocene voles of southern Spain. Evidence from other small vertebrates at this site such as amphibians and squamates revealed a change from the pre-Olduvai levels of the Galera section (Galera�2, Guadix-Baza Basin), characterized by warm and rather humid conditions, towards drier, less humid, seasonal conditions at Barranco de los Conejos (Agust� et al. 2013). Among insectivores, the absence of Crocidurinae at this site can be interpreted in the same way. This is also confirmed by the clear dominance of the murid Castillomys rivas, a taxon linked to open grassy areas, against the scarce representation of Apodemus atavus, more related to forests (although Apodemus could have also consumed abrasive plants; Gomes Rodrigues et al. 2013). The entry at this time of eastern immigrants, such as Tibericola vandermeuleni and the ovibovine bovids of the genus Praeovibos is also indicative of the spread to the west of the more arid conditions prevailing during the Early Pleistocene in the Mediterranean Levant. Therefore, the endemic rodent fauna from Barranco de los Conejos can be interpreted as a local response to the Early Pleistocene glacial�interglacial dynamics.

Conclusions

The site of Barranco de los Conejos presents a peculiar rodent association, characterized by three arhizodont arvicoline species: Orcemys giberti, Manchenomys oswaldoreigi, and Tibericola vandermeuleni. This association strongly differs from other coeval Early Pleistocene sites from Europe, such as Schernfeld, Villany-5, Betfia-2, Kamyk, and Mas Rambault (Kowalski 1960; Chaline 1972; Meulen 1974; Garapich and Nadachowski 1996), which are characterized by the presence of the first representatives of Allophaiomys (Allophaiomys deucalion, Allophaiomys pliocaenicus). The Barranco de los Conejos sample includes two endemic species, Orcemys giberti and Manchenomys oswaldoreigi, which probably derived from local representatives of the genus Mimomys (Mimomys medasensis, Mimomys tornensis). The only exotic element is Tibericola vandermeuleni, a species whose closest relatives have been found in the Early Pleistocene sites from Turkey and Israel. The presence of Tibericola at Barranco de los Conejos is most probably the consequence of a dispersal event from the eastern to the western Mediterranean, an event which also included the first ovibovines of the genus Praeovibos. The trend towards loosening of roots in Orcemys and Manchenomys can be explained as an adaptation to the new environmental conditions forced by the glacial�interglacial dynamics of the Early Pleistocene, which in the case of the lower latitudes of southern Spain led to drier and cooler conditions, as it is also indicated by the prevalence of the murid Castillomys rivas against Apodemus atavus at Barranco de los Conejos. This change in the climatic conditions was most probably responsible for the western dispersal of eastern elements such as Tibericola and Praeovibos.

Acknowledgements

The authors would here like to express their gratitude to Adam Nadachowski (Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals, Krak�w, Poland) and Helder Gomes Rodrigues (Mus�um National d�Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France) for their comments, which contributed to ameliorate the paper. IPHES is part of the CERCA Pro�gram (Generalitat de Catalunya) and has received financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through the �Mar�a de Maeztu� program for Units of Excellence (CEX2019-000945-M). This research is also supported by projects PRP-PID2021-123092NB-C21 (Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation), 2021SGR-1238 (AGAUR-Generalitat de Catalunya), and P20_00066 (Junta de Andaluc�a). One author (PP) is supported by a �Juan de la Cierva-Incorporaci�n� contract (grant IJC2020-044108-I) funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and �European Union Next�GenerationEU/PRTR�.

References

Adrover, R., Mein, P., and Moissenet, E. 1993. Roedores de la transici�n Mio-Plioceno de la regi�n de Teruel. Paleontologia i Evoluci� 26�27: 47�84.

Aguilar, J.P., Crochet, J.Y., Hebrard, O., Le Strat, P., Michaux, J., and Pedra, S. 2002. Les micromammiferes de Mas Rambault 2, gisement karstique du Pliocene sup�rieur du Sud de la France: �ge, pal�oclimat, g�odynamique. G�ologie de la France 4: 17�37.

Aguilar, J.P., Michaux, J., Delannoy, J.J., and Guendon, J.L. 1993. A Late Pliocene rodent fauna from Alozaina (Malaga, Spain). Scripta Geologica 103: 1�22.

Agust�, J. 1986. Synthese biostratigraphique du Plio Pleistocene de Guadix Baza (province de Granada, sud est de l�Espagne). Geobios 19: 505�510. Crossref

Agust�, J. 1991. The Allophaiomys complex in Southern Europe. Geobios 25: 133�144. Crossref

Agust�, J., Blain, H.-A. Furi�, M., Marf�, R. De, Mart�nez-Navarro, B., and Oms, O. 2013. Early Pleistocene environments and vertebrate dispersals in Western Europe: the case of Barranco de los Conejos. Quaternary International 295: 59�68. Crossref

Agust�, J., Blain, H.-A., Lozano-Fern�ndez, I., Pinero, P., Oms, O., Furi�, M., Blanco, A., L�pez-Garc�a, J. and Sala, R. 2015a. Chronological and environmental context of the first hominin dispersal into Western Europe: the case of Barranco Le�n (Guadix-Baza Basin, SE Spain). Journal of Human Evolution 87: 87�94. Crossref

Agust�, J., Castillo, C., and Galobart, A. 1993. Heterochronic evolution in the Late Pliocene�Early Pleistocene arvicolids of the Mediterranean area. Quaternary International 19: 51�56. Crossref

Agust�, J., Chochishvili, G., Lozano-Fern�ndez, I., Furi�, M., Pinero, P., and De Marfa, R. 2022a. Small mammals (Insectivora, Rodentia, Lagomorpha) from the Early Pleistocene hominin-bearing site of Dmanisi (Georgia). Journal of Human Evolution 170: 103238. Crossref

Agust�, J., De Marfa, R., and Santos-Cubedos, A. 2010. Roedores y lagomorfos (Mammalia) del Pleistoceno inferior de Barranco Le�n 5 y Fuente Nueva 3 (Orce, Granada). In: I. Toro, B. Mart�nez-Navarro, and J. Agust� (eds.), Ocupaciones humanas en el Pleistoceno inferior y medio de la cuenca de Guadix-Baza, 121�140. Consejer�a de Cultura, Sevilla.

Agust�, J., Lozano-Fern�ndez, I., Oms, O., Pinero, P., Furi�, M., Blain, H.-A., L�pez-Garc�a, J.M., and Mart�nez-Navarro B. 2015b. Early to Middle Pleistocene rodent biostratigraphy of the Guadix-Baza Basin. Quaternary International 389: 139�147. Crossref

Agust�, J., Moya Sola, S., and Pons Moya, J. 1987. La sucesi�n de mam��feros en el Pleistoceno inferior de Europa: proposici�n de una nueva escala bioestratigr�fica. Paleontologia i Evoluci� (Memoria Especial) 1: 287�295.

Agust�, J., Oms, O., and Par�s, J.M. 1999. Calibration of the Early�Middle Pleistocene transition in the continental beds of the Guadix-Baza Basin (SE Spain). Quaternary Science Reviews 18: 1409�1417. Crossref

Agust�, J., Oms, O., Garc�s, M., and Par�s, J.M. 1997. Calibration of the late Pliocene�Early Pleistocene transition in the continental beds of the Guadix Baza Basin (South Eastern Spain). Quaternary International 40: 93�100. Crossref

Agust�, J., Pinero, P., Lozano-Fern�ndez, I., and Jim�nez-Arenas, J.J. 2022b. A new genus and species of arvicolid rodent (Mammalia) from the Early Pleistocene of Spain. Comptes Rendus Palevol 21: 847�858. Crossref

Agust�, J., Santos-Cubedo, A., Furi�, M., De Marf�, R., Blain, H.A., Oms, O., and Sevilla, P. 2011. The late Neogene�early Quaternary small vertebrate succession from the Almenara-Casablanca karst complex (Castell�n, Eastern Spain): chronologic and paleoclimatic context. Quaternary International 243: 183�191. Crossref

Bachelet, B. 1990. Muridae et Arvicolidae (Rodentia, Mammalia) du Plio�cene du Sud de la France: syst�matique, �volution, biochronologie. 211�pp. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Universit� de Montpellier II, Montpellier.

Burckle, L.H. 1995. Current Sigues in Pliocene paleoclimatology. In: E.S. Vrba, G.H. Denton, and T.C. Partridge (eds.), Paleoclimate and Evolution, with Emphasis on Human Origins, 3�7. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Cai, C. and Qiu, Z. 1993. Murid rodents from the late Pliocene of Yangquan and Yuxian, Hebei. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 31: 267�293.

Castillo Ruiz, C. 1990. Paleocomunidades de Micromam�feros de los yaci�mien�tos k�rsticos del Ne�geno Superior de Andaluc�a Oriental. 225 pp. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada.

Castillo, C. and Agust�, J. 1996. Early Pliocene rodents (Mammalia) from Asta Regia (Jerez Basin, Southwestern Spain). Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen 99: 25�43.

Chaline, J. 1972. Les Rongeurs du Pleistoc�ne moyen et superieur de France. (Systematique, Biostratigraphie, Pal�oclimatologie). Cahiers de Paleontologie, CNRS 6: 1�410.

Chaline, J. 1987. Arvicolid data (Arvicolidae, Rodentia) and evolutionary concepts. Evolutionary Biology 21: 237�310. Crossref

Colombero, S., Pavia, G., and Carnevale, G. 2014. Messinian rodents from Moncucco Torinese, NW Italy: palaeobiodiversity and biochronology. Geodiversitas 36: 421�475. Crossref

Duval, M., Falgueres, C., Bahain, J.-J., Gr�n, R., Shao, Q., Aubert, M., Hellstrom, J., Dolo, J.-M., Agust�, J., Mart�nez-Navarro, B., Palmqvist, P., and Toro-Moyano, I. 2011. The challenge of dating Early Pleistocene fossil teeth by the combined US-ESR method: the case of Venta Micena palaeontological site (Orce, Spain). Journal of Quaternary Science 26: 603�615. Crossref

Esteban Aenlle, J. and L�pez Mart�nez, N. 1987. Les arvicolid�s (Rodentia, Mammalia) du Villanyen recent de Casablanca 1 (Castell�n, Espagne). Geobios 20: 591�623. Crossref

Fejfar, O. and Storch, G. 1990. Eine Plioz�ne (ober-Ruscinische) Klein�s�igerfauna aus Gunsdersheim, Rhein-hessen. 1. Nagetiere: Mam�ma�lia, Rodentia. Senkenbergiana Lethaea 71: 139�184.

Garapich, A. and Nadachowski, A. 1996. A contribution to the origin of Allophaiomys (Arvicolidae, Rodentia) in Central Europe: the relationship between Mimomys and Allophaiomys from Kamyk (Poland). Acta Zoologica Cracoviensia 39: 179�184.

Garc�a-Alix, A., Minwer-Barakat, R., Mart�n-Su�rez, E., and Freudenthal, M. 2008. Muridae (Rodentia, Mammalia) from the Mio-Pliocene boundary in the Granada Basin (southern Spain). Biostratigraphic and phylogenetic implications. Neues Jahrbuch fur Geologie und Palaontologie Abhandlungen 248: 183�215. Crossref

Gomes Rodrigues, H., Renaud, S., Charles, C., Le Poul, Y., Sol�, F., Aguilar, J.P., Michaux, J., Tafforeau, P., Headon, D., Jernvall, J., and Viriot, L. 2013. Roles of dental development and adaptation in rodent evolution. Nature Communications 4: 2504. Crossref

Heller, F. 1936. Eine oberplioz�ne Wirbeltierfauna aus Rheinhessen. Neues Jahrbuch f�r Mineralogie, Geologie und Pala�ntologie, Abteilung B 76: 99�160.

Hordijk, K. and De Bruijn, H. 2009. The succession of rodent faunas from the Mio-Pliocene lacustrine deposits of the Florina-Ptolemais-Servia Basin (Greece). Hellenic Journal of Geosiences 44: 21�103.

H�sing, S.K., Oms, O., Agust�, J., Garc�s, M., Kouwenhoven, T.J., Krijgsman, W., and Zachariasse, W.-J. 2010. On the late Miocene closure of the Mediterranean-Atlantic gateway through the Guadix basin (southern Spain). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeocology 291: 167�179. Crossref

Janis, C.M. 1988. An estimation of tooth volume and hypsodonty indices in ungulate mammals, and the correlation of these factors with dietary preferences. M�moires du Mus�um national d�Histoire naturelle de Paris 53: 367�387.

Knitlov�, M. and Hor��ek, I. 2017. Late Pleistocene�Holocene paleobiogeography of the genus Apodemus in central Europe. PLoS One 12: e0173668. Crossref

Kowalski, K. 1960. An Early Pleistocene fauna of small mammals from Kamyk (Poland). Folia Auaternaria 1: 1�24.

L�pez-Garc�a, J.M., Pinero, P., Agust�, J., Furi�, M., Gal�n, J., Moncunill-�Sol�, B., Ruiz-S�nchez, F.J., Blain, H.-A., Sanz, M., and Daura, J. 2023. Chronological context, species occurrence, and environmental remarks on the Gelasian site Pedrera del Corral d�en Bruach (Barcelona, Spain) based on the small-mammal associations. Historical Bio�logy [published online, https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2180740]. Crossref

Lordkipanidze, D., Jashashvili, T., Vekua, A., Ponce de L��n, M., Zollikofer, C., Rightmire, G.P., Pontzer, H., Ferring, R., Oms, O., Tappen, M., Buk�hsia�nidze, M., Agust�, J., Kahlke, R., Kiladze, G., Mart�nez-Navarro, B., Mouskhelishvili, and Nioradze, M. 2007. Postcranial evidence from �early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia. Nature 449: 305�310. Crossref

Marchetti, M., Parolin, K., and Sala, B. 2000. The Biharian fauna from Monte La Mesa (Verona, northeastern Italy). Acta Zoologica Craco�viensia 43: 79�105.

Martin, L.D. 1984. Phyletic trends and evolutionary rates. In: M. Dawson and H. Genoways (eds.), Festshrift for J. Guilday. Carnegie Museum of Natural History (Special Publication) 8: 526�538.

Martin, L.D. 1993. Evolution of hysodonty and enamel structure in Plio-�Pleistocene rodents. In: R.A. Martin and A.D. Barnosky (eds.), Morphological Change in Quaternary mammals of North America, 205�225. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Crossre

Martin, R.A., Tesakov, A., Agust�, J., and Johnston, K. 2018. Orcemys, a new genus of arvicolid rodent from the Early Pleistocene of the Guadix-�Baza Basin, southern Spain. Comptes Rendus Palevol 17: 310�319.

Mart�n-Su�rez, E. 1988. Sucesiones de micromam�feros en la Depresi�n de Guadix-Baza (Granada, Espana). 241 pp. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada. Crossref

Mart�n-Su�rez, E. and Freudenthal, M. 1993. Muridae (Rodentia) from the lower Turolian of Crevillente (Alicante, Spain). Scripta Geologica 103: 65�118.

Mart�n-Su�rez, E. and Mein P. 1991. Revision of the genus Castillomys (Muridae, Rodentia). Scripta Geologica 96: 47�81.

Mart�n-Su�rez, E.M. and Mein, P. 1998. Revision of the genera Parapodemus, Apodemus, Rhagamys and Rhagapodemus (Rodentia, Mammalia). Geobios 31: 87�97.

Mart�n-Su�rez, E. and Mein, P. 2004. The late Pliocene locality of Saint-�Vallier (Dr�me, France). Eleven micromammals. Geobios 37: 115�125. Crossref

Maul, L.C., Masini, F., Parfitt, S.A., Rekovets, L., and Savorelli, A. 2014. Evolutionary trends in arvicolids and the endemic murid Mikrotia�new data and a critical overview. Quaternary Science Reviews 96: 240�258. Crossref

Mein, P., Moissenet, E., and Adrover, R. 1990. Biostratigraphie du N�ogene Sup�rieur du bassin de Teruel. Paleontologia i Evoluci� 23: 121�139.

Mein, P., Moissenet, E., and Truc, G. 1978. Les formations continentales du N�ogene sup�rieur des vall�es du J�car et du Cabriel au ne d�Alba�cete (Espagne). Biostratigraphie et environnement 72: 99�148.

Meulen, A.J. van der 1973. Middle Pleistocene smaller mammals from the Monte Peglia (Orvieto, Italy) with special reference to the phylogeny of Microtus (Arvicolidae, Rodentia). Quaternaria 17: 1�144.

Meulen, A.J. van der 1974. On Microtus (Allophaiomys) deucalion (Kretzoi, 1969), (Arvicolidae, dentia), from the Upper Villanyian (Lower Pleistocene) of Villany-5, S. Hungary. Proceedings Koninkl? ke Neder�landse Akademie van Wetenschappen B 77: 259�266.

Michaux, J. 1967. Origine du dessin dentaire Apodemus (Rodentia, Mammalia). Comptes Rendus de l�Acad�mie des Sciences Paris 265: 711�714.

Michaux, J. 1969. Muridae (Rodentia) du Pliocene sup�rieur d�Europe et du Midi de la France. Palaeovertebrata 3: 1�25. Crossref

Michaux, J. 1971. Arvicolinae (Rodentia) du Plioc�ne terminal et du Quatemaire ancien de France et d�Espagne. Palaeovertebrata 4: 137�214. Crossref

Minwer-Barakat, R., Garc�a-Alix, A., Mart�n-Su�rez, E., and Freudenthal, M. 2005. Muridae (Rodentia) from the Pliocene of Tollo de Chiclana (Granada, south-eastern Spain). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25: 426�441. Crossref

M�rs, T., Von Koenigswald, W., and Von der Hocht, F. 1998. Rodents (Mammalia) from the late Pliocene Reuver Clay of Hambach (Lower Rhine Embayment, Germany). Mededelingen Nederlands Instituut voor Toegepaste Geowetenschappen 60: 135�160.

Oms, O., Agust�, J., Gabas, M., and Anad�n, P. 2000. Lithostratigraphical correlation of micromammal sites and biostratigraphy of the Upper Pliocene to Lower Pleistocene in the Northeast Guadix-Baza Basin (Southern Spain). Journal of Quaternary Science 15: 43�50. Crossref

Oms, O., Anad�n, P., Agust�, J., and Julia, R. 2011. Geology and chronology of the continental Pleistocene archeological and paleontological sites of the Orce area (Baza basin, Spain). Quaternary International 243: 33�43. Crossref

Pasquier, L. 1974. Dynamique �volutive d�un sous-genre de Muridae Apodemus (Sylvaemus). Etude biom�trique des caracteres dentaires de populations fossiles et actuelles d�Europe occidentale. 176 pp. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Universit� de Montpellier, Montpellier.

Pinero, P. and Agust�, J. 2019. The rodent succession in the Sif�n de Librilla section (Fortuna Basin, SE Spain): implications for the Mio-Pliocene boundary in the Mediterranean terrestrial record. Historical Bio�logy 31: 279�321. Crossref

Pinero, P. and Agust�, J. 2020. Rodents from Botardo-D and the Miocene�Pliocene transition in the Guadix-Baza Basin (Granada, Spain). Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments 100: 903�920. Crossref

Pinero, P., Agust�, J., and Oms, O. 2018a. The late Neogene rodent succession of the Guadix-Baza Basin (south-eastern Spain) and its magnetostratigraphic correlation. Palaeontology 61: 253�272. Crossref

Pinero, P., Agust�, J., Blain, H.A., Furi�, M., and Laplana, C. 2015. Biochronological data for the Early Pleistocene site of Quibas (SE Spain) inferred from rodents assemblage. Geologica Acta 13: 229�241.

Pinero, P., Agust�, J., Furi�, M., and Laplana, C. 2018b. Rodents and insectivores from the late Miocene of Romerales (Fortuna Basin, Southern Spain). Historical Biology 30: 336�359. Crossref

Pinero, P., Agust�, J., Laborda, C., Duval, M., Zhao J.-X., Blain, H.A., Furi�, M., Laplana, C., Rosas, A., and Sevilla, P. 2022. Quibas-Sima: a unique 1 Ma-old vertebrate succession in southern Iberian Peninsula. Quaternary Science Reviews 283: 107469. Crossref

Pinero, P., Agust�, J., Oms, O., Blain, H.A., Furi�, M., Laplana, C., Sevilla, P., Rosas, A., and Vallverd�, J. 2020. First continuous pre-Jaramillo to Jaramillo terrestrial vertebrate succession from Europe. Scientific Reports 10: 1901. Crossref

Pinero, P., Agust�, J., Oms, O., Blain, H.A., Laplana, C., Ros-Montoya, S., and Mart�nez-Navarro, B. 2017. Rodents from Baza-1 (Guadix-Baza Basin, southeast Spain): filling the gap of the early Pliocene succession in the Betics. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 37 (4): e1338294. Crossref

Pinero, P., Mart�n-Perea, D.M., Sevilla, P., Agust�, J., Blain, H.A., Furi�, M., and Laplana, C. 2023. La Piquera in central Iberian Peninsula: A�new key vertebrate locality for the Early Pliocene of western Europe. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 68: 23�46. Crossref

Rabeder, G. 1981. Die arvicoliden (Rodentia, Mammalia) aus dem Plioz�n und dem �lteren Pleistoz�n von Nieder�sterreich. Beitr�ge zur Pal�ontologie �sterreichs 8: 1�373.

Rietschel, S. and Storch, G. 1974. Aussergew�hnlich erhaltene Waldm�use (Apodemus atavus Heller, 1936) aus dem Ober-Plioz�n von Willershausen am Harz. Senckenbergiana Lethaea 54: 491�519.

Ruiz Bustos, A., Ses�, C., Dabrio, C.J., Pena Ruano, J.A., and Padial, J.M. 1984. Geolog�a y fauna de micromam�feros del nuevo yacimiento del Plioceno inferior de Gorafe-A (Depresi�n de Guadix-Baza, Granada). Estudios Geol�gicos 40: 231�241. Crossref

Sevilla, P., Esteban, Aenlle, J., and L�pez-Mart�nez, N. 1991. Interpre�taci�n de los cambios morfol�gicos observados en tres poblaciones sucesivas de Mimomys medasensis de Casablanca (Castell�n) en funci�n de heterocron�as del desarrollo. Revista Espanola de Paleontolog�a 6: 20�24. Crossref

Toro-Moyano, I., Mart�nez-Navarro, B., Agust�, J., Souday, C., Berm�dez de Castro, J. M., Martin�n-Torres, M., Fajardo, B., Duval, M., Falgueres, C., Oms, O., Par�s, J.M., Anad�n, P., Julia, R., Garc�a-Agui�lar, J.M., Moigne, A.-M., Espigares, M.P., Ros-Montoya, S., and Palmqvist, P. 2013. The oldest human fossil in Europe, from Orce (Spain). Journal of Human Evolution 65: 1�9. Crossref

�nay, E., Emre, �., Erkal, T., and Ke�er, M. 2001. The rodent fauna from the Adapazari pull-apart basin (NW Anatolia): its bearings on the age of the North Anatolian Fault. Geodinamica Acta 14: 169�175. Crossref

Vekua, A., Lordkipanidze, D., Rightmire, G.P., Agust�, J., Ferring, R., Maisuradze, G., Mouskhelishvili, A., Nioradze, M., Ponce de Le�n, M., Tappen, M., Tvalchreridze, M., and Zollikofer, C. 2002. A new skull of early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia. Science 297: 85�89. Crossref

Weerd, A. van de 1976. Rodent faunas of the Mio-Pliocene continental sediments of the Teruel-Alfambra region, Spain. Utrech Micropaleontological. Bulletin, Special Publication 2: 1�217.

Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 68 (2): 379�391, 2023

https://doi.org/10.4202/app.01074.2023